Switzerland was reshaped considerably by industrialisation in the time between the founding of the federal state in 1848 and the turn of the century. The population grew from 2.4 to 3.3 million. An increasing number of men and women moved from rural areas to cities and became wage earners in industry and commerce. Zurich, Basel and Geneva became urban economic centres. City walls were torn down and replaced by new peripheral districts. The liberal economic system and technical innovations facilitated the construction of railways and factories. Machine-making progressively replaced the textile industry as the driving economic force. Export business flourished and a modern services sector with banks and insurance firms emerged.

This development was by no means trouble-free. Growth spurts were hampered by crises. Wealth and general opportunities in life remained highly unevenly distributed. Broad swathes of the population continued to be at risk of poverty. With mobility increasing and new forms of employment such as factory work emerging, families and local communities were less and less able to absorb the effects of poverty and social plight. At the same time, the early liberal state continued to limit public assistance to the poor and left many aspects of welfare to private charities, cooperative and union relief funds and the church.

The general public initially disputed the problem of poverty, referring to it as ‘pauperism’. The term ‘social question’ was coined around 1850. It was better suited to the situation of the growing working class and accounted for the emergence of a reformist (i.e. non-revolutionary) wing of the working class. Initially, an important role in this debate was played by charitable organisations, which propagated the ethos of self-help and regarded poverty as being a consequence of deficient morals. The economic crisis in the 1870s and the erosion of the liberal societal model enabled the idea of state-led “social reform” to gain traction among the bourgeois elite too. The notion that the state has an obligation to ‘represent the common interests’ for the benefit of socially disadvantaged groups and intervene in economic life with the support of experts widely caught on. How and to what extent, however, remained subject to debate

Literatur / Bibliographie / Bibliografia / References: Degen Bernard (2006), Entstehung und Entwicklung des schweizerischen Sozialstaates, Studien und Quellen, 31, 17–48; Studer Brigitte (1998a), Soziale Sicherheit für alle? Das Projekt Sozialstaat 1848–1998, in B. Studer (ed.), Etappen des Bundesstaates. Staats- und Nationsbildung in der Schweiz, 159–186, Zürich; HLS / DHS / DSS: Soziale Frage.

(12/2014)

In Switzerland, assisting people unable to support themselves was traditionally one of the duties incumbent on the municipalities. The principle of support in one’s hometown held firm until well into the 20th century. People in need from other municipalities were sent back to their home municipalities by means of ‘pauper carts’. This made it more difficult for the poor to find employment as they could only receive support in their home municipalities. The increasing legal rules on poverty increased the influence of the cantons on poor relief, while the powers of the federal state remained limited. The introduction of the ‘alcohol tenth’ in 1887 was the first time federal funding became available to the cantons to counter alcoholism or inadequate upbringing – both of which were considered significant causes of poverty at the time.

In particular, the elderly, women and children were threatened by poverty. A moralizing view of poverty was prevalent among the bourgeois elite: only the ‘deserving’ poor, those unable to work as a result of age, youth, family obligations, illness or disability, were to receive support. Whereas poor people capable of working were accused of improvidence, prodigality or lacking work ethic. Structural causes of poverty were ignored. Although mass poverty decreased after 1850, economic slumps continued to be a threat to people.

In an effort to address poverty, the cantons and municipalities expanded elementary schools and adapted the system of relief to new social emergencies (handing over tasks to private associations and later replacing the hometown principle with one that supported the poor in their place of residence). Likewise, they promoted emigration, set up poorhouses and reformatories for the destitute elderly and children or took repressive measures (such as workhouses, marriage prohibitions and suspension of voting rights), which further stigmatized already peripheral groups in society.

Literatur / Bibliographie / Bibliografia / References: Head Anne-Lise, Schnegg Brigitte (ed.) (1989), Armut in der Schweiz (17.–20. Jh.), Zürich; Lippuner Sabine (2005), Bessern und Verwahren: Die Praxis der administrativen Versorgung von „Liederlichen“ und „Arbeitsscheuen“ in der thurgauischen Zwangsarbeitsanstalt Kalchrain (19. und frühes 20. Jahrhundert), Frauenfeld.

(12/2014)

Assistance funds were a link between traditional forms of provision (as provided by guilds, for example) and modern social insurance schemes. The first funds – organized as unions – emerged as early as the end of the 18th century. By the 1870s, they became prevalent particularly in industrialized regions and cities. In 1888, Switzerland had 1,085 assistance funds serving 209,920 members. In industrial regions, up to 25 percent of the workforce were members of such a fund. Though a number of funds were open to anyone; most were maintained by professional associations, employers or trade unions.

Unlike poor relief, the assistance funds were geared towards the working population, in particular the growing industrial workforce. They were based on the principle of mutuality and the balance of risk: the members were required to regularly pay a premium and, in return, received a modest daily allowance protecting them in the event of loss of earnings due to illness or disability. Special burial funds assumed the burial costs for policyholders. From the 1880s, a number of funds also offered pensions for old age, widows and orphans, and competed with commercial insurers such as the Swiss life insurance and pensions company, Swisslife, founded in 1857.

In the 1860s, insurance mathematicians like Herrmann Kinkelin or Johann Jakob Kummer began to criticize the organization and financial models of the assistance funds for their inadequate capital reserves, which rendered the funds incapable of fulfilling their obligations in the long run. However, the assistance funds resisted calls for controls and rejected a state health and accident insurance scheme – particularly in French-speaking Switzerland. Yet, the introduction of accident insurance in 1918 strengthened state regulation and competition. The number of funds dropped after the First World War. Some became commercial insurers.

Literatur / Bibliographie / Bibliografia / References: Lengwiler Martin (2006), Risikopolitik im Sozialstaat: Die schweizerische Unfallversicherung (1870–1970), Köln; Muheim David (2000), Mutualisme et assurance maladie (1893–1912). Une adaptation ambigue, Traverse, 2, 79–93.

(12/2014)

In 1877, despite resistance from the industry, the electorate narrowly voted in favor of federal legislation regarding factory work – this became known as the Factory Act. This constituted the direct intervention of the Confederation in economic affairs: it curbed freedom of contract and the autonomy of industrialists. Switzerland thus became a pioneer in relation to protecting workers’ rights.

During the 1860s, non-profit groups and doctors drew attention to the topic of working conditions with their investigations revealing inadequacies in terms of fatal hazards and health risks in factories as well as the prevalence of child labor. Subsequently, the protection of factory workers’ health and productivity dominated the debate regarding the ‘social question’. The completely revised federal constitution of 1874 ultimately gave the Confederation the power to pass regulations concerning child Labour, the limitation of working hours and the protection of workers.

In many respects, the Swiss Factory Act implemented the constitutional standard built on the legislation of those cantons, which had already regulated industrial work. The canton of Zurich, for instance, had introduced restrictions to child Labour in 1815. The act passed by the canton of Glarus in 1864 led the way for the development of workers’ protection, as it regulated the employment of adults for the first time. The Swiss Factory Act limited working hours to eleven hours per day, and prohibited work at night and on Sundays. It also banned the employment of children less than 14 years of age and pregnant women a number of weeks prior to and after childbirth. It committed factory owners to adhere to provisions for the protection of workers and made them liable in the event of accidents, while inspectors monitored compliance with the law. However, it only applied to factories, but not to the many small commercial enterprises, let alone agriculture. In 1882, only 134,500 people or around 10 percent of the workforce were covered by the new legislation.

Literatur / Bibliographie / Bibliografia / References: Siegenthaler Hansjörg (ed.) (1997), Wissenschaft und Wohlfahrt. Moderne Wissenschaft und ihre Träger in der Formation des schweizerischen Wohlfahrtsstaates während der zweiten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts, Zürich; Gruner Erich (1968), Die Arbeiter in der Schweiz im 19. Jahrhundert, Bern.

(12/2014)

Between 1883 and 1889, the German Reich introduced the obligatory health and accident insurance system as well as old age and disability insurance for workers and other wage earners. Soon, the new model of provision was also discussed and propagated in Switzerland. It marked the transition from social policy intended for welfare and the swift repair of damages to an expandable public service based on individual legal entitlements and social insurance that covered the risks of working life. Several factors tipped the scales in favor of the reforms initiated by Imperial Chancellor Otto von Bismarck: an interventionist understanding of the role of the state, problems with the existing assistance funds, unresolved questions regarding accident coverage and the intention of the government to integrate the working class into the authoritarian state and thus weaken social democracy.

The German health insurance (1883) included coverage of treatment costs, daily sickness allowance, and support for women in childbed and death benefits. The accident insurance (1884) likewise covered treatment costs and further provided for accident prevention measures. The old age and disability insurance (1889) granted a modest pension in the event of occupational disability or upon reaching the age of 70. All three insurance schemes were mandatory for people with an annual income of less than 2,000 Reichsmarks. They were funded by contributions from employees and employers, and additionally – in the case of old age and disability insurance – by state subsidies. The insurance schemes were either introduced on the basis of existing health insurance funds or new self-governing trade associations (accident insurance) and regional insurance institutions (old age and disability insurance) were set up.

Literatur / Bibliographie / Bibliografia / References: Lengwiler Martin (2007b), Transfer mit Grenzen: das ‚Modell Deutschland‘ in der schweizerischen Sozialstaatsgeschichte 1880–1950, in G. Kreis, R. Wecker (ed.), Deutsche und Deutschland aus Schweizer Perspektiven, 47–66, Basel; Stolleis Michael (2003), Geschichte des Sozialrechts in Deutschland, Stuttgart; Kott Sandrine (1995), L’état social allemand. Représentations et pratiques, Paris.

(12/2014)

The constitutional article that granted the Confederation the power to set up a mandatory accident and health insurance system was passed with a decisive majority in the popular vote of 26th October 1890. It transferred responsibilities from the cantonal level to the Confederation and represented a significant step towards national welfare policy. The new constitutional article drew impetus from civil liability in occupational accidents, which had led to dissatisfaction on the part of both workers and business owners. Whereas workers ran the risk of coming away empty-handed from a case, business owners carried all of the responsibility of buying their employees into a collective policy with an insurance company. The predominantly bourgeois Parliament instructed the Federal Council in 1885 to start preparations for the introduction of a mandatory workers’ accident insurance. In the course of these preparations, the Federal Council incorporated health insurance into the bill.

The Federal Council commissioned several statistical surveys and ordered a number of expert reports, including the notable memorandum by Ludwig Forrer, a National Councillor from the canton of Zurich affiliated to the Free Democratic Party. He advocated the insurance principle (‘spreading the risk to many’) and the establishment of a mandatory public accident and health insurance following the model set by Bismarck: ‘liability means dispute, insurance means peace.’ The Federal Council and Parliament followed this visionary, pragmatic concept. However, the proposal submitted by the advising committee of the National Council to expand the legislative powers of the Confederation to include ‘other types of personal insurance’ and lay the constitutional foundation for old age, disability or unemployment insurance straight away did not gain acceptance.

Literatur / Bibliographie / Bibliografia / References: Lengwiler Martin (2006), Risikopolitik im Sozialstaat: Die schweizerische Unfallversicherung (1870–1970), Köln; Degen Bernard (1997), Haftpflicht bedeutet den Streit, Versicherung den Frieden: Staat und Gruppeninteressen in den frühen Debatten um die schweizerische Sozialversicherung, in H. Siegenthaler (ed.), Wissenschaft und Wohlfahrt. Moderne Wissenschaft und ihre Träger in der Formation des schweizerischen Wohlfahrtstaates während der zweiten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts, 137–154, Zürich.

(12/2014)

The Swiss welfare state began to take shape between 1890 and 1947. The creation of a constitutional basis for an accident and health insurance in 1890 represented a first step towards modern social policy. But in 1900, voters rejected a bill for a health and accident insurance act. It was only with considerable delay that politicians were able to save parts of the bill. Eleven years later, a much more streamlined bill was passed in a next referendum; the bill only prescribed mandatory accident insurance. This was to become a familiar pattern in the establishment of social security leading up to the Second World War. The period seems like a protracted phase of experimentation distinguished by gradual, minimalistic and sometimes unsuccessful attempts at reform. Lasting impetus even failed to take hold after the First World War and the general national strike of 1918, which triggered social activism in the short term. The system of direct democracy, plebiscites as well as political negotiations in the run up to referenda all had an impeding effect. This also explains how the first moderate bill for old age and survivors’ insurance failed to secure a majority in 1931. It was only the experiences of the Second World War that enabled the emergence of new momentum, ultimately culminating in the introduction of the AHV (old age and survivors’ insurance) in 1947.

This development resulted in social security in Switzerland remaining a hybrid and heterogeneous system until well after the Second World War. Not only the state (federation, cantons and municipalities) played an important role, but many private stakeholders too: commercial insurance companies as well as charitable and non-profit organisations for example. The major burden borne by public welfare continued to be communal poor relief, which, however, developed new strategies for dealing with social plight after the turn of the century.

Literatur / Bibliographie / Bibliografia / References: Studer Brigitte (2012), Ökonomien der sozialen Sicherheit, in P. Halbeisen, M. Müller, B. Veyrasset (ed.), Wirtschaftsgeschichte der Schweiz im 19. Jahrhundert, 923–974, Basel; Degen Bernard (2006), Entstehung und Entwicklung des schweizerischen Sozialstaates, Studien und Quellen, 31, 17–48.

(12/2014)

At the turn of the 20th century, the system of municipal poor relief still formed the backbone of social welfare. The principle of support in one’s home municipality was retained by most cantons. Nevertheless, new approaches for improving the situation of workers and for tackling poverty emerged around 1900, as did measures for controlling and disciplining the lower classes. As part of a drive for ‘communal social policy’, it was predominantly the cities that expanded their social provision. For instance, the city of Bern established an employment office in 1889, a poorhouse in 1892 and an unemployment fund in 1893. Bern also encouraged the construction of social housing and subsidized private day nurseries and crèches (1891/1898).

At the same time, a new generation of welfare experts – who gathered at the 1905 Swiss Conference on Poor Relief – called for the rationalization of welfare following examples set abroad. Guidelines were established for caseworkers, the centralization of organization, the bureaucratization of procedures and the professionalization of personnel. Social schools founded by women opened up the vocational field of welfare work for bourgeois women.

The new understanding of welfare was visible in an exemplary manner in how cities cared for youths. Further development and scientific attention accompanied the child protection provisions of the Civil Code (1912) as well as the institutionalization of education and training courses (from 1908). The city of Zurich thus professionalized the medical care of school children (1905) and reorganized the system of guardianship (1908). Public welfare was thereby expanded from children in need to ‘neglected’ and sick children. In this process, the authorities increasingly involved scientific experts, especially doctors and remedial educators.

Literatur / Bibliographie / Bibliografia / References: Matter Sonja (2011), Der Armut auf den Leib rücken: Die Professionalisierung der Sozialen Arbeit in der Schweiz (1900–1960), Zürich; Tabin Jean-Pierre et al. (2010 [2008]), Temps d’assistance. L’assistance publique en Suisse romande de la fin du XIXe siècle à nos jours, Lausanne; Schnegg Brigitte (2007), Armutsbekämpfung durch Sozialreform: Gesellschaftlicher Wandel und sozialpolitische Modernisierung Ende des 19. Jahrhunderts am Beispiel der Stadt Bern, Berner Zeitschrift für Geschichte und Heimatkunde, 69, 233–258; Ramsauer Nadja (2000), “Verwahrlost”: Kindswegnahmen und die Entstehung der Jugendfürsorge im schweizerischen Sozialstaat, 1900–1945. Zürich.

(12/2014)

On the occasion of the 1900 World Exhibition in Paris, social policymakers from various European countries founded the International Association for Labour Legislation (IALL). It established an International Labour Office in Basel that was largely funded by Switzerland. Just like the many other international congresses as well as international organisations and offices that emerged at the turn of the century, the foundation of the IALL reflected the growing economic interdependence of modern industrial countries and the development of modern transport and communication links. Matters of social security figured high on the international congress agenda. Experts and officials debated public welfare and private charity as well as occupational accidents, insurance schemes and the methods applied in actuarial science (for calculating insurance risks).

It was no coincidence that Switzerland was committed to workers’ protection beyond its borders. The Factory Act of 1877 contained special provisions for the protection of children and women, and was widely considered to be progressive. Representatives of the working class, industry and the Federal Council were all equally interested in harmonizing protection provisions the terms of competition across borders. After an initial diplomatic push failed in 1890, the workers’ union organized a congress in Zurich in 1897 that sought to coordinate international social policy.

After its foundation, the International Labour Office in Basel acted primarily as a documentation center. Further to its role as a private association close to government, the IALL initiated several conventions, including protection from hazardous substances and a ban of night work for women. Until the First World War, it continued to push for the protection of young workers and for the introduction of an eight-hour workday. Many of its functions were transferred to the International Labour Organization in 1919.

Literatur / Bibliographie / Bibliografia / References: Herren-Oesch Madeleine (2009), Internationale Organisationen seit 1865. Eine Globalgeschichte der internationalen Ordnung, Darmstadt; Topalov Christian (1999), Laboratoires du nouveau siècle. La nébuleuse réformatrice et ses réseaux en France, 1880-1914, Paris; Garamvölgyi Judit (1982), Die internationale Vereinigung für gesetzlichen Arbeiterschutz, in Gesellschaft und Gesellschaften. Festschrift Ulrich Im Hof, 626–646, Bern.

(12/2014)

On 20th May 1900, around 70 percent of voters rejected the federal bill on health, accident and military insurance despite the support of all political parties and trade associations. The electorate followed the arguments of a broad opposition comprising liberal anti-centrists in western Switzerland, conservatives, private insurance companies and some members of the agricultural and working class communities. In particular, anti-statist arguments presented by health and assistance funds that feared for their autonomy caught on with the voters.

The bill passed with a large majority in the Federal Assembly in October 1899 had been drafted by National Councillor Ludwig Forrer. The FDP politician was at the forefront of the push for social security. Although the complex, 400 articles strong legislative proposal was limited to employed workers, it represented a major step forward. For the first time, it prescribed mandatory insurance for most wage earners, while offering others the option of voluntary insurance. Soldiers would also have been covered. The insurance would not only have assumed treatment costs, but also included illness, childbed and death benefits allowances. The accident and military insurance would have granted coverage of disability and survivors’ pensions too. The insurance was to be funded by federal contributions as well as employer and employee premiums. Parliament intended to hand over implementation to both existing private health insurance funds and new public funds yet to be created, as well as to the planned Swiss Institute for Accident Insurance. A federal insurance court was envisaged as the relevant appellate court.

The voters' rejection of the bill brought an abrupt end to the dream of comprehensive risk cover. As a result, further social welfare development was dependent on small increments in policy during the following decades. Nevertheless, military insurance commenced provision already in 1902. And in 1912, voters accepted a more streamlined version of the health and accident insurance bill; it was limited to mandatory accident insurance and contained no fundamental reforms to health insurance.

Literatur / Bibliographie / Bibliografia / References: Degen Bernard (1997), Haftpflicht bedeutet den Streit, Versicherung den Frieden: Staat und Gruppeninteressen in den frühen Debatten um die schweizerische Sozialversicherung, in H. Siegenthaler (ed.), Wissenschaft und Wohlfahrt. Moderne Wissenschaft und ihre Träger in der Formation des schweizerischen Wohlfahrtstaates während der zweiten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts, 137–154, Zürich.

(12/2014)

Efforts to provide support to injured soldiers in Switzerland and other European countries reach back into the early modern period. Military pension schemes have been in place in the Confederation since 1852 and 1875. An accident insurance scheme was also set up for parts of the troops by private initiative in 1887. At the same time, the Confederation was working on a comprehensive health and accident insurance solution that was to cover not only the industrial workforce, but soldiers too. However, the draft bill of 1900 (Lex Forrer) was rejected by referendum. The federal authorities subsequently decided to split the uncontested military insurance from the more controversial parts of the proposal. The Federal Act on the Insurance of Military Persons Against Illness and Accident was swiftly passed in 1901 and entered into force in 1902. This represented the birth of the first social insurance in Switzerland.

The introduction of Swiss military insurance showed that in the case of injured soldiers the principle of insurance had prevailed over welfare. The Confederation no longer restricted compensation to people in need, but extended the benefits to members of the armed forces depending on the duration and severity of injury. Though the insurance only covered illnesses and accidents that occurred during military service, it did comprise illnesses and injuries not directly related to a military activity. However, no benefits were granted for pre-existing conditions that recurred or worsened during service. The insurance benefits included free meals and treatment up to complete recovery an illness allowance and, where applicable, a disability pension for soldiers as well as death benefits or survivors’ pensions for their next of kin.

Literatur / Bibliographie / Bibliografia / References: Militärversicherungs-Schriftenreihe, 1, 1976 u. 2, 1979; Maeschi Jürg (2000), Kommentar zum Bundesgesetz über die Militärversicherung (MVG) vom 19. Juni 1992, Bern; Morgenthaler W. (1939), Militärversicherung, in Handbuch der schweizerischen Volkswirtschaft, 179-80, Bern.

(12/2014)

After a quarter of a century of intense debate, voters finally accepted the Federal Act on Health and Accident Insurance (KUVG) on 4th February 1912. With respect to accident insurance, the KUVG broadly conformed to the Lex Forrer proposal previously rejected in the 1900 referendum. However, the mandatory insurance covered a smaller demographic range and was limited to employees in industry and to certain professions. Until the 1980s, only about half of the employed workforce had mandatory insurance against accidents, though there was a growing number of voluntary policyholders. The benefits (treatment costs, illness allowance, pensions and death benefits) and funding of the accident insurance were similar in scope to the 1900 proposal. However, the bill did not include mandatory health insurance. It was the cantons that subsequently passed such obligations. The Confederation’s involvement remained restricted to the subsidization and regulation of private funds.

The new act transferred the implementation of the accident insurance to Suva (the Swiss Institute for Accident Insurance), which began its work as an autonomous public-law entity in Lucerne in 1918. To this day, the highest decision-making body in Suva is the administrative board comprised of representatives of employers, employees and the Confederation. The administrative board also appoints the board of directors. Suva’s responsibilities include accident prevention, a task previously assigned to factory inspectors. In addition, Suva has been committed to the field of medical rehabilitation for many years, in particular by running a health spa facility in Baden (1928).

Literatur / Bibliographie / Bibliografia / References: Lengwiler Martin (2006), Risikopolitik im Sozialstaat: Die schweizerische Unfallversicherung (1870–1970), Köln.

(12/2014)

On 19th December 1912, Parliament approved the formation of the Federal Social Insurance Office (BSV) – the first federal agency to be designated as a federal office. It was assigned to the Department for Trade, Industry and Agriculture (now known as the Federal Department of Economic Affairs, Education and Research) and was initially accommodated in the building of the Swiss National Bank in Bern. Its tasks included the execution of the Health and Accident Insurance Act (KUVG), in particular the supervision of Suva, and the recognition and subsidization of health insurance funds. In addition, the office was responsible for further preparations regarding social insurance and for international agreements. It was appointed with six regular positions: a director, an assistant, an expert, a mathematician and two clerks.

The new administrative unit constituted an institutional outcome of the referendum on 4th February 1912 with which the KUVG was passed. From the very beginning, the Federal Council intended to ensure the new office had access to the necessary actuarial expertise and was directed by ‘qualified insurance experts’. First it was supposed to merge the new office with the Swiss Insurance Office (known today as the Federal Office of Private Insurance) responsible for monitoring private insurance companies since 1886, an idea that was soon discarded. Following a rejection from the insurance office director and mathematician, Christian Moser, the decision was eventually reached that insurance lawyer, Hermann Rüfenacht, would occupy the position of director.

Another reason for the creation of a new office was the fact that old age and disability insurance still figured on the political agenda. The ‘insurance problems’ were by no means solved with the introduction of the KUVG. The Federal Council held the view that, in future, the state would have to be in a position to carry out and justify the ‘objectively necessary development of its legislature’ and recognize the ‘economic consequences’: “Only then may government bodies defend workable measures with energy and authority, and also be able to confront excessive demands beyond our powers with objective reasons.”

Literatur / Bibliographie / Bibliografia / References: Bundesamt für Sozialversicherungen (1988), Geschichte, Aufgaben und Organisation des Bundesamtes fürs Sozialversicherung (Sonderdruck aus der Zeitschrift für die Ausgleichskassen, 1988, Nr. 7–9), Bern; Botschaft des Bundesrates an die Bundesversammlung betreffend die Errichtung eines Bundesamtes für soziale Versicherung, 29. Oktober 1912, Bundesblatt, 1912 IV, 501–526.

(12/2014)

Like all European counties at the outbreak of the First World War, Switzerland only expected a short engagement. No socio-political measures were taken to counter the rampant inflation for a long time. Neither was there compensation of loss of pay for soldiers nor price controls. It was not until the final two years of the war that authorities began rationing basic food such as milk and bread. The Federal Council also softened the Factory Act and ordered wage freezes in public enterprises. The results were losses of real earnings ranging from 25 to 30 percent as well as shortages in food and housing. In the summer of 1918, official statistics indicated 692,000 people – around one sixth of the population – were in need of emergency aid. These figures were even higher in cities. The already weakened population was then hit by the Spanish flu in autumn 1918 which claimed almost 25,000 lives – or 0.6 percent of the population by 1920.

Emergency measures were implemented primarily by the cantons and municipalities. Often in cooperation with non-profit women’s associations, they set up soup kitchens and workers’ shelters, and handed out food. The Confederation chiefly supported unemployment welfare. It predicted a rise in unemployment and therefore established a welfare fund in 1917 that was funded through war taxes. The Confederation worked with municipalities and employers to support people who had become unemployed through no fault of their own. In addition, the Confederation subsidized existing unemployment funds, often set up by the unions, and alleviated the tax burden for private pension schemes.

The worsening social situation brought about a polarization in domestic politics as well as protests and strikes. These developments culminated in the National General Strike in November 1918. The Olten action committee, which coordinated the workers’ movement, primarily demanded social policies, namely: women’s right to vote, the 48-hour week, the safeguarding of food supply and the introduction of an old age and disability insurance which had been stalled at the political level since 1912.

Literatur / Bibliographie / Bibliografia / References: Tabin Jean-Pierre et al. (2010 [2008]), Temps d’assistance. L’assistance publique en Suisse romande de la fin du XIXe siècle à nos jours, Lausanne.

(12/2014)

Prior to 1914, there were only a limited number of pension funds outside the public sector and just a handful of companies granted their employees an old age pension. This changed after 1916, when the Confederation decided to exempt contributions to pension schemes from the war profit tax. This tax exemption led to the formation of a whole range of new pension funds, particularly in the machine-making and metal industry. The number of funds increased ten-fold (from around one hundred to over one thousand) between 1911 and 1930. However, this boom concealed some considerable differences among workers: in 1930, two thirds of public-sector workers were members of a pension plan, while this figure was only at ten percent for private-sector workers.

Beyond tax optimization, employers’ pension schemes also played their part in soothing working relations after the National General Strike and strengthening employees’ loyalty to their companies. The delays and obstacles in establishing the AHV can also explain this initial phase of expansion. From the interwar period on, the private provision lobby, which banded together in 1922 in the Swiss Association of Support Funds and Foundations for Retirement and Disability (SVUSAI), became an important actor in the pension debates.

The life insurers also held a strategic position in these debates. Drawing on their expertise in actuarial mathematics (the method for calculating insurance risks), they were able to advise the Confederation in the initial AHV projects. From the 1920s these companies also entered the pensions market, thanks to group contracts (for companies that wanted to offer pension benefits without having to run their own pension fund). Private pensions enjoyed considerable financial clout: at the start of the Second World War, pension reserves already amounted to more than a quarter of the gross domestic product.

Literatur / Bibliographie / Bibliografia / References: Leimgruber Matthieu (2008), Solidarity without the state? Business and the shaping of the Swiss welfare state, 1890–2000, Cambridge; Leimgruber Matthieu (2006), La politique sociale comme marché. Les assureurs vie et la structuration de la prévoyance vieillesse en Suisse (1890–1972), Studien und Quellen, 31, 109–139, Zürich.

(12/2014)

The International Labour Organization (ILO) was founded in 1919 on the basis of the Treaty of Versailles and in connection with the League of Nations. The ILO and its affiliated International Labour Office, still based in Geneva, took a leading role in international workers’ protection and transnational social policy after the First World War. The ILO was founded on the notion that a stable peace among nations could only be achieved through the cooperation of employers, unions and the state. The International Association for Labour Legislation– the government-related precursor to the ILO – only afforded the workers and unions’ movement a subordinate role. This changed with the ILO: all national delegations in this organization are comprised of two official delegates plus a representative of employees and employers respectively.

Before the ILO began its work, the first International Labour Conference took place in Washington. The conference passed twelve draft agreements, which stipulated the introduction of the 48-hour week, measures against unemployment and protection for women, mothers and youths in industry. These resolutions were particularly significant for Switzerland as they put the demand for financial maternity protection on the political agenda. While the Federal Council and Parliament rejected the ratification of the corresponding convention for financial reasons, they did pass other special protections for women. The Federal Social Insurance Office was nevertheless commissioned to review the integration of maternity protection in health insurance. Yet, the reform was not passed until the mid-1920s. Another legislative proposal suffered the same fate just before the outbreak of the Second World War. In general, Switzerland long delayed its ratification of ILO conventions until the Second World War. In most cases, these conventions broadened the scope of social security. Altogether, only three of the 15 agreements were adopted.

Literatur / Bibliographie / Bibliografia / References: Herren-Oesch Madeleine (2009), Internationale Organisationen seit 1865. Eine Globalgeschichte der internationalen Ordnung, Darmstadt; Wecker Regina, Studer Brigitte, Sutter Gaby (2001), Die ‚schutzbedürftige Frau‘. Zur Konstruktion von Geschlecht durch Mutterschaftsversicherung, Nachtarbeitsverbot und Sonderschutzgesetzgebung, Zürich; Kneubühler Helen Ursula (1982), Die Schweiz als Mitglied der Internationalen Arbeitsorganisation, Bern.

(12/2014)

The Federal Council and Parliament had already rejected a proposal to create unemployment insurance prior to the First World War. Mandatory insurance was also not stipulated by the 1924 federal act on the payment of contributions. Indeed, the Confederation merely increased contributions into existing public and private unemployment funds. The socio-political function of unemployment support was thus delegated to 61 funds in total – most of which were provided by unions and insured around 185,000 people in 1923.

This regulation only encompassed ten percent of the workforce and largely built on the practice of existing unemployment funds and the municipalities. In 1884, the Swiss Association of Typographers founded the first unemployment fund and other occupational sectors soon followed suit. After the turn of the century, several cantons began to subsidies these funds following the example set by the Belgian city of Gent. In turn, the Confederation promoted job placement from 1909. In terms of policy, however, Parliament and Federal Council put off an insurance solution as demanded by the working class. Due to an impending rise in unemployment figures, the municipalities, cantons and the Confederation finally decided to expand welfare for the unemployed in need as from 1917. Concurrently, the Confederation became involved in the system of the cantons based on the Gent model. Once the remaining crisis measures were lifted, this financial plan persisted and became law in 1924.

This law led to an upturn in unemployment funds, albeit modest. In 1936, 204 funds provided insurance for 552,000 people. Roughly 28 percent of the workforce was thus insured. After all, around half the cantons had by then declared the insurance as mandatory. In contrast, the union funds were somewhat weakened since the regulation of 1924 granted them lower contributions compared to those of public and parity funds. This, though, was so intended by of the bourgeois majority in Parliament.

Literatur / Bibliographie / Bibliografia / References: Tabin Jean-Pierre, Togni Carola (2013), L’assurance chômage en Suisse. Une socio-histoire (1924-1982), Lausanne.

(12/2014)

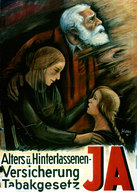

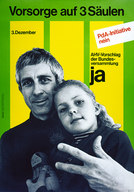

On 6th December 1925, voters were called to the polling stations to decide on the AHV for the first time. Two thirds of voting men and 16½ cantons supported the constitutional basis for the introduction of compulsory AHV. The Confederation was also given the authority to introduce disability insurance at a later date. Following the Health and Accident Insurance Act of 1912 and the framework legislation on unemployment insurance in 1924, this represented the next step towards achieving social security that was no longer founded on welfare, but rather the individual legal entitlements of people insured.

Following the model of social insurance set by Bismarck, left-leaning circles within the bourgeoisie and sections of the workers’ movement had called for the introduction of old age, survivors’ and disability insurance (AHIV) already in the 1880s. They had done so, for instance, during the debate on the constitutional basis for the subsequent Health and Accident Insurance Act (KUVG). AHIV figured prominently on the parliamentary agenda in 1912, but discourse on the matter was delayed by the outbreak of war. By 1918, the basic principle behind the AHIV was uncontested. Even the bourgeois parties professed to an interest in the welfare state. They also hoped concessions to the left wing would alleviate tension after the National General Strike. The Federal Council presented its first draft AHIV bill in 1919.

However, the drive for social policy reform did not last. In view of the post-war crisis, strengthening bourgeois interests called the funding model proposed by the Federal Council into question. Particular controversy surrounded the question of whether direct taxes should be increased to fund the AHIV – as envisaged in the draft initiative of 24th May 1925 by FDP National Councillor Christian Rothenberger. In an effort to prevent the project from being defeated, the Federal Council proposed – under the leadership of Edmund Schulthess – to forego disability insurance and purge the bill of controversial aspects. Parliament agreed to this compromise, though it intended to pursue disability insurance at a later date. The new Article 34quater stipulated few binding commitments with regard to funding, benefits or the organization of the new insurance scheme (now dubbed AHV). These matters would require further legislative clarification.

Literatur / Bibliographie / Bibliografia / References: Leimgruber Matthieu (2008), Solidarity without the state? Business and the shaping of the Swiss welfare state, 1890–2000, Cambridge; Pellegrini Luca (2006), L’assurance vieillesse, survivants et invalidité : ses enjeux finanicer entre 1918 et 1925, Studien und Quellen, 31, 79–107; Lasserre André (1972), L'institution de l'assurance-vieillesse et survivants (1889–1947), in R. Ruffieux (ed.), La démocratie référendaire suisse au 20ème siècle, 259–326, Fribourg.

(12/2014)

On 6th December 1931, 60 percent of voters rejected the first AHV bill, which would have implemented the old age and survivors’ insurance that had been approved in principle in 1925. The highbrow Neue Zürcher Zeitung referred to the outcome as a ‘catastrophic defeat’ for the welfare state. Indeed, the rejected bill was rather modest in scope. It aimed to achieve merely a ‘minimum level of welfare’ – as the Federal Council put it. It stipulated mandatory insurance, standard pensions (200 francs per year upon reaching 66 years of age) and allowances for those in need. The contribution-based funding system was based on percentages of wages as well as duties on alcohol and tobacco. A decentralized structure comprising cantonal insurance funds was planned for the necessary organization. Under the bill, the cantons would have been authorized to set up supplementary insurance, provided there was no conflict with private occupational pension schemes. By 1931, five cantons already offered modest old age benefits.

Despite criticism from the Social Democratic Party concerning the minimal social welfare included in the bill and the rather cautious attitude prevalent in industry, the bill garnered the approval of all major parties and associations. However, the looming global economic crisis proved expedient for the opponents of the AHV who pushed anticentralist and antimodernist views. Just like in the rejection of Lex Forrer (1900), opponents of the bill formed a highly heterogeneous coalition: liberal conservatives from western Switzerland and representatives of the agricultural community stood against impending ‘statism’ and purportedly excessive insurance contributions, while Catholic conservatives considered state insurance a threat to individual responsibility and private welfare. Shortly before the vote, the referendum committee presented a welfare initiative that proposed an alternative to the AHV based on means tests. As a result of the defeated AHV bill, poverty relief remained a matter of municipal welfare until after the Second World War, except for cases covered by private or cantonal insurance.

Literatur / Bibliographie / Bibliografia / References: Leimgruber Matthieu (2008), Solidarity without the state? Business and the shaping of the Swiss welfare state, 1890–2000, Cambridge; Lengwiler Martin (2003), Das Drei-Säulen-Konzept und seine Grenzen: private und berufliche Altersvorsorge in der Schweiz im 20. Jahrhundert, Zeitschrift für Unternehmensgeschichte, 48, 29–47.

(12/2014)

The Great Depression posed a major challenge to the state. The crisis hit Switzerland relatively late due in part to the country’s upturn in the second half of the 1920s. However, the economy did not recover until 1937. National income fell by almost 20 percent as a result of the crisis. In the winter of 1936, the unemployment rate spiked at seven percent of the workforce and was even higher in industrial regions. The burden on the population was further exacerbated by the deflationary economic policy pursued by the bourgeois parties and business associations. They held on to the gold parity of the Swiss franc, ran contradictory domestic and taxation policies, cut wages and only took selective action in the economy, for the benefit of the agricultural sector for example. The bourgeois parties battled against deficit spending as stipulated by the defeated 1935 «crisis initiative» proposed by the federation of trade unions.

The crisis and hesitant economic policy bore bitter consequences: the number of people in need of aid soared to almost 20 percent of the population. In Neuchâtel and other cities, the welfare budget doubled between 1929 and 1937. Elderly or people with disabilities who only had limited financial means were hit particularly hard. As they had done in the First World War and post-war periods, cities again set up soup kitchens, workers’ shelters and emergency accommodation. Still less than a third of working men and a fifth of working women were insured against unemployment. The disbursements and membership figures of unemployment funds therefore soared during the crisis. At the end of 1931, the Confederation re-established support for jobseekers no longer entitled to benefits, which had been suspended in 1924. However, it left the major burden of unemployment aid to the cantons and municipalities. It was not until pressure came from the left-wing crisis initiative that the Confederation became involved in job creation. The effects of which, however, were not palpable until the devaluation of the Swiss franc in September 1936 and the gradual economic recovery.

Literatur / Bibliographie / Bibliografia / References: Müller Margrit, Woitek Ulrich (2012), Wohlstand, Wachstum und Konjunktur, in P. Halbeisen, M. Müller, B. Veyrasset (ed.), Wirtschaftsgeschichte der Schweiz im 19. Jahrhundert, 91–222, Basel; Tabin Jean-Pierre et al. (2010 [2008]), Temps d’assistance. L’assistance publique en Suisse romande de la fin du XIXe siècle à nos jours, Lausanne.

(12/2014)

In 1935, the US Congress passed the Social Security Act (SSA), which marked the beginning of social security in the USA. Public welfare in the USA was considered to be rather rudimentary in the early 1930s. Apart from provisions for war veterans, only few states provided unemployment or old age insurance. A mere 15 percent of workers were insured by private pension funds. The SSA formed part of the New Deal with which President Franklin D. Roosevelt intended to tackle the consequences of the Great Depression (rising unemployment and mass poverty) and stimulate the economy and reform social order. In addition, he took a number of measures to counteract unemployment, stabilize the banking sector, and control prices and working conditions.

In 1935, the SSA encompassed old age insurance as well as allowances for federal aid programs; survivors’ insurance was added in 1939 and disability insurance in 1955. Old Age Insurance (OAI) was based on a system of contributions, rendering funded reserves unnecessary. Following the Second World War, many pension schemes in numerous other countries followed this example. The OAI was financed by wage deductions, half of which were paid by employees and employers respectively. This was also intended to lead to the reconciliation of social classes. The SSA was implemented step by step: by 1937, insurance cards were issued and the administrative structure set up; the first pensions were distributed in 1940. However, the process of consolidation lasted up until 1949. Coverage was gradually expanded to include more contributors. The SSA had no negative influence on the development of supplementary pension plans (occupational provision) as its benefits offered only covered basic needs – as was the case with the subsequent Swiss AHV.

Literatur / Bibliographie / Bibliografia / References: Leimgruber Matthieu (2008), Solidarity without the state? Business and the shaping of the Swiss welfare state, 1890–2000, Cambridge; Website Social Security Administration, Social Security History: www.ssa.gov/history.

(12/2014)

At first glance, the Second World War brought about significant innovation in the development of Swiss social security. Between 1938 and 1944, the share of gross domestic product attributed to social expenditures rose from 4.7 to 6.9 percent – a level that would not be reached again until the mid-1950s. In contrast to the situation that had prevailed during the First World War, the Income Compensation Insurance for Militia Soldiers (LVEO) offered income support against war-related income-loss, made a significant contribution towards avoiding social conflict and increasing national solidarity. The EO formed the organizational and financial foundation for the old age and survivors’ insurance (AHV), which represented a breakthrough for the principle of compulsory social insurance when it was introduced in 1947.

Despite these developments, socio-political change remained modest both during and after the Second World War. The social expenditure ratio thus declined after the war and only began to rise again in 1949. Social welfare was only expanded within the frame of the AHV, which meant extremely low pensions and plenty of room for occupational provision managed by employers. For instance, there was still no mandatory health or unemployment insurance. Though the constitutional groundwork for maternity insurance and family allowances was laid in 1945, its introduction was delayed by decades. There was also major continuity with respect to organization: Centralization proceeded sluggishly and key social policy fields remained based on decentralized structures (such as equalization funds and private insurance) or on the principle of voluntarism (health insurance and occupational provision).

Literatur / Bibliographie / Bibliografia / References: Leimgruber Matthieu, Lengwiler Martin (ed.) (2009), Umbruch an der ‚inneren Front‘. Krieg und Sozialpolitik in der Schweiz 1938–1948, Zürich.

(12/2014)

At the outbreak of the Second World War, the top priority was to ensure the financial protection of soldiers and their families. During the First World War, the lack of a safety net had been a key factor in exacerbating social tensions as soldiers serving in the military had no access to income other than their military pay. After the war, the state was under no obligation to compensate soldiers for their loss of earnings. The private sector had different regulations depending on the industry and employee category. On 20th December 1939, the Federal Council therefore decided to introduce a system for compensating income loss. This was expanded in 1940 into the Income Compensation Insurance for Militia Soldiers (LVEO), which also covered the self-employed. The insurance was financed by contributions from employers and employees (two percent of earnings each) as well as subsidies from the Confederation and the cantons. It protected up to 90 percent of the income of married soldiers. However, the benefits for unmarried soldiers remained modest. The Confederation left much leeway to employers to manage the LVEO with the equalization funds set up by business associations. At this point, the Central Compensation Fund (ZAF) was the only federal institution involved and was mainly responsible for balancing the accounts of each of the funds.

After accident insurance, the LVEO constituted the second compulsory social insurance branch in Switzerland. It quickly gained substantial popularity. It was soon treated as a model for the AHV. However, the LVEO provided no protection from loss of earnings and poverty. Its relatively generous scope was also aimed at reducing incentives for married women to enter employment. The LVEO thus made a substantial contribution to the stabilization of bourgeois gender roles and family values.

By 1947, the LVEO had paid out a total of 1.64 billion francs. At the same time, the ZAF surpluses rose to 1.165 billion francs. Most of these funds were to be used as seed money for the AHV in 1947, which greatly increased the likelihood of the new social welfare system being implemented. After the war, LVEO financing relied on capital reserves and federal contributions until its reorganization in 1958/1961.

Literatur / Bibliographie / Bibliografia / References: Leimgruber Matthieu (2009), Schutz für Soldaten nicht für Mütter. Lohnausfallentschädigung für Dienstleitende und Sozialversicherungen in der Schweiz, in M. Leimgruber, M. Lengwiler (ed.), Umbruch an der ‚inneren Front‘. Krieg und Sozialpolitik in der Schweiz 1938–1948, 75–99, Zürich.

(12/2014)

The Report to Parliament on Social Insurance and Allied Services was published in the United Kingdom in November 1942. Shortly after the Battle of El Alamein – the first major victory of the Allies against the German Wehrmacht – this document constituted an important propaganda tool. Over 600,000 copies were distributed. The author, economist and welfare state expert William Henry Beveridge, had investigated social insurance systems on behalf of the British Government. He outlined a model of social security in which all citizens paid a weekly contribution into a national insurance scheme and, in return, were protected against risks to one’s livelihood such as illness, disability or unemployment. Beveridge argued that it was the duty of the state to stand by its citizens from the cradle to the grave and to combat the five ‘giant evils’: plight, illness, ignorance, squalor and idleness. Beveridge’s proposals for expanding and consolidating social welfare into a comprehensive public insurance system based on a national spread of risk were incorporated into reform programs by the Labour government which took over Churchill’s coalition government in the summer of 1945. The social insurance schemes were expanded and gaps in the welfare system closed in just a short period of time. The National Health Service commenced its work in 1948. These reforms were embedded in extensive planning and nationalization programs.

The welfare model put forward by Beveridge was also met with great interest in Switzerland. However, discourse quickly became dominated by an emphasis on national differences. This was reflected by the Bohren Report of the Federal Social Insurance Office (BSV) published in May 1943 which concluded that the Beveridge plan was neither compatible with Switzerland's federalist state system, nor with the involvement of non-state stakeholders – not to mention the financial requirements such a plan would entail. Discussion regarding the expansion of social security, which also took place in Switzerland in 1942, thus remained limited to certain fields of social provision, especially the AHV and family protection.

Literatur / Bibliographie / Bibliografia / References: Leimgruber Matthieu, Lengwiler Martin (ed.) (2009), Umbruch an der ‚inneren Front‘. Krieg und Sozialpolitik in der Schweiz 1938–1948, Zürich; Monachon Jean-Jacques (2002), Le plan Beveridge et les débats sur la sécurité sociale en Suisse entre 1942 et 1945, in H.-J. Gilomen, S. Guex, B. Studer (ed.), De l’assistance à l’assurance sociale. Ruptures et continuités du Moyen Age au XXe siècle, 321–329, Zürich.

(12/2014)

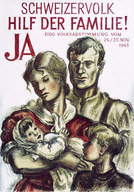

On 25th November 1945, voters accepted a counterproposal of the Federal Council and Parliament for the popular initiative ‘For the Family’. The new Article 34quinquies enshrined family protection in the federal constitution and gave the Confederation the authority to create legislation in the area of family compensation funds, to introduce maternity insurance and to support the construction of housing and estates for the benefit of families. In contrast, the withdrawn initiative would have explicitly declared the family as the ‘foundation of state and society’ and demanded the Confederation to base its economic and social policy completely on the needs of families. It also involved the formation of compensation funds offering family or child allowances.

By launching the popular initiative ‘For the Family’, the Catholic Conservative Party entered the debate on post-war order with a socio-political draft based closely on Catholic social doctrine. Since their focus was placed on the ‘natural unit’ of the family and traditional gender roles, the initiative claimed to offer an alternative to the AHV advocated by the Socialists and the FDP. However, in view of falling birth rates and rising divorce rates, the notion of protecting the family gained momentum far beyond Catholics in the 1930s – such as in the Family Protection Commission of the Swiss Philanthropic Society (SGG), which included female representatives from the Union of Swiss Women’s Associations. Also, numerous family compensation funds had already been created before the end of the war.

The socio-political postulates accepted in January 1945 subsequently remained subordinate concerns of the welfare state. The family compensation funds were to a large extent regulated either on a private or cantonal level. It was not until 2006 that a federal act laid the groundwork for harmonization. Attempts to introduce maternity benefits failed in 1984, 1987 and 1999. A solution finally emerged in 2004 as part of the income compensation scheme.

Literatur / Bibliographie / Bibliografia / References: Schumacher Beatrice (2009), Familien(denk)modelle. Familienpolitische Weichenstellungen in der Formationsphase des Sozialstaats (1930–1945), in M. Leimgruber, M. Lengwiler (ed.), Umbruch an der ‚inneren Front‘. Krieg und Sozialpolitik in der Schweiz 1938–1948, 139–164, Zürich; Hauser Karin (2004), Die Anfänge der Mutterschaftsversicherung. Deutschland und Schweiz im Vergleich, Zürich; Studer Brigitte (1997), Familienzulagen statt Mutterschaftsversicherung? Die Zuschreibung der Geschlechterkompetenzen im sich formierenden Schweizer Sozialstaat, 1920–1945, Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Geschichte, 47, 151–170.

(12/2014)

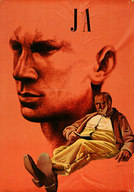

On 6th July 1947, the electorate voted in favor of introducing the AHV. On the same day, voters also accepted to revise the economic articles of the federal constitution that gave the Confederation the right to intervene in the economy in the overall interest of the country. It also enshrined the involvement of economic associations. Both resolutions laid the groundwork for basic compromise in the post-war period.

The new welfare system stipulated a retirement age of 65 years for both men and women. It offered old age, widows’ and orphans’ pensions to be funded through contributions by employees and employers, subsidies from and the Confederation and cantons. The pensions were so modest that they did not compete with private provision (basic AHV pension: 40 to 125 francs per month for an average monthly industrial wage of 745 francs). Income-tested pensions were provided for the generation that had already reached retirement. In terms of organization, the AHV adopted the decentralized system of the associations and cantonal compensation funds that had been established with the Income Compensation Insurance for Militia Soldiers (LVEO).

The AHV was created as a direct result of the political change that had also reached Switzerland in 1942/1943. The victory of the Allied Powers seemed inevitable by then and new socio-political options opened up with the Beveridge Report. In 1942, a popular initiative supported by the left wing and the FDP demanded that the LVEO should be converted into the AHV. After initial hesitation, the Federal Council set up an expert commission at the beginning of 1944 and presented a bill to Parliament two years later. Drawing on its legal powers, in October 1945 the Federal Council also met a demand made by the Federation of trade unions and provisionally redirected LVEO surpluses into old age provision. Parliament later confirmed this decision and thus solved the funding problem concerning the AHV. The AHV act enjoyed the support of an overwhelming parliamentary majority. Nevertheless, as had been the case with the AHV proposal of 1931, a coalition of Liberals from western Switzerland Catholic Conservatives and business representatives launched a referendum. This time, though, over 80 percent of the electorate delivered a sweeping endorsement of the AHV.

Literatur / Bibliographie / Bibliografia / References: Leimgruber Matthieu (2008), Solidarity without the state? Business and the shaping of the Swiss welfare state, 1890–2000, Cambridge; Luchsinger Christine (1995), Solidarität, Selbständigkeit, Bedürftigkeit: der schwierige Weg zu einer Gleichberechtigung der Geschlechter in der AHV: 1939-1980, Zürich; Luchsinger Christine (1994), Sozialstaat auf wackligen Beinen. Das erste Jahrzent der AHV, in J.-D. Blanc, C. Luchsinger (ed.), achtung: die 50er Jahre! Annäherungen an eine widersprüchliche Zeit, 51–69, Zürich.

(12/2014)

Social insurance remained relatively underdeveloped until the Second World War. Real socio-political change only came after the outbreak of war. In 1931, a first attempt to introduce the public AHV had failed due to federalist concerns regarding centralized public institutions. Conversely, private provision enjoyed an upswing in the interwar period.

The decades following 1945 were characterized by the successive introduction of new insurance branches and mandatory schemes: the AHV (1948), disability insurance (IV, 1960), income-tested supplementary benefits (EL, 1966), unemployment insurance (ALV, 1976) and occupational old age provision (BVG. 1985). There were also reforms in social assistance. Between 1950 and 1990, the social expenditure ratio (a quotient comparing social insurance expenditures with the gross domestic product) also rose significantly. This ratio provides insight into the relative importance of social insurance expenditures in relation to economic activity. The ratio stood at ten percent in 1950; in 1973 it had reached 15 percent and 21 percent by 1990.

Initially, the welfare state was developed against the backdrop of post-war prosperity with high growth rates, rising wages, full employment and expanding government activity. This growth period faltered in the mid-1970s, while the period leading up to 1990 was characterized by fluctuating economic performance. It was during these decades that growing concern about the further expansion of the welfare state took hold among bourgeois parties, as well as business and small employers' associations. Consolidation and selective reforms to the existing welfare system thus came to the fore.

Despite the singular period of expansion, social security in Switzerland remained patchy for a long time. Compared to other industrialized countries, the social expenditure ratio remained rather low until 1990. Well until the 1970s, social insurance schemes remained minimal, for example in the domain of unemployment. There was still no mandatory health insurance; the introduction of maternity insurance and family allowances was delayed for decades, although they had been approved in principle in 1945.

Literatur / Bibliographie / Bibliografia / References: Studer Brigitte (2012), Ökonomien der sozialen Sicherheit, in P. Halbeisen, M. Müller, B. Veyrasset (ed.), Wirtschaftsgeschichte der Schweiz im 19. Jahrhundert, 923–974, Basel.

(12/2015)

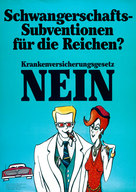

On 22nd May 1949, a majority of voters rejected an amendment to the Tuberculosis Act of 1928. The proposal by the Federal Council and Parliament primarily proposed periodic check-ups for the population on the basis of newly developed screening technology. It enabled the quick and reliable identification of the infected, but not yet ill people – often referred to as carriers or spreaders at the time. Political opposition that led to a referendum and derailed the proposal was not only directed against the forced medical exams and the costs involved, but also against the fact that the proposal would have introduced mandatory health insurance for low-income social groups.

Health insurers had previously offered voluntary tuberculosis insurance in addition to general health insurance. This practice was supported by contributions from the Confederation. In 1946, three quarters of health insurance policyholders benefited from this form of supplementary insurance. This amounted to less than half of the overall population. The rejected proposal was based on the premise that infected people unable to afford treatment could pose a threat to the health of others. The proposed compulsory insurance would have therefore served first and foremost as prophylaxis.

During the referendum campaign, the controversial question remained as to whether the Confederation sought to introduce compulsory health insurance through the back door in tandem with the amended Tuberculosis Act. The proposal suffered a resounding defeat at the ballot with 75 percent of the electorate saying no. The Confederation and administration interpreted the result as a rejection of compulsory health insurance in general.

Literatur / Bibliographie / Bibliografia / References: Lengwiler Martin (2009), Das verpasste Jahrzehnt. Krankenversicherung und Gesundheitspolitik (1938–1949), in M. Leimgruber, M. Lengwiler (ed.), Umbruch an der ‹inneren Front›. Krieg und Sozialpolitik in der Schweiz 1938–1948, 165–184, Zürich; Gredig Daniel (2002), Von der „Gehilfin“ des Arztes zur professionellen Sozialarbeiterin. Professionalisierung in der sozialen Arbeit und die Bedeutung der Sozialversicherungen am Beispiel der Tuberkulosenfürsorge Basel (1911–1961), in: H.-J. Gilomen, S. Guex, B. Studer (ed.), Von der Barmherzigkeit zur Sozialversicherung. Umbrüche und Kontinuitäten vom Spätmittelalter bis zum 20. Jahrhundert, 221–241, Zürich; Immergut Ellen M. (1992), Health Politics. Interests and Institutions in Western Europe, Cambridge.

(12/2014)

The postwar economic boom would not have been possible without the mass immigration of foreign workers. In 1950, 285,000 foreign nationals were present in Switzerland was at; twenty years later this number had soared to 1,080,000 (an increase from 6.1 to 17.2 percent of the population). A large portion of immigrants initially came from Italy, followed by other countries in southern Europe, such as Spain, Portugal and Yugoslavia. Residence permits were usually issued for a limited duration, meaning that the majority of foreign workers had to leave Switzerland for a while after less than one year - a mechanism that became known as the rotation principle. Permanent residence and the admission of family dependents became easier only from the 1960s onwards. However, immigration policy tightened against the backdrop of increasingly xenophobic sentiment, as manifested in the Schwarzenbach popular initiative against ‘foreign infiltration’ (Überfremdung). In response, the Confederation took measures to stabilize the proportion of foreign residents, for instance by prescribing quotas and contingents for individual companies and countries of origin.

Social insurance was also affected by the recruitment of foreign workers. In 1929, Switzerland had acceded to a convention of the International Labour Organization (ILO), which sought to prevent discrimination in accident insurance. Foreign workers began paying into the AHV from the very beginning, without necessarily being able to claim benefits later. Switzerland also entered into bilateral social insurance agreements with a number of countries governing the provision of benefits abroad in particular. For instance, the 1949, 1951 and 1962 agreements with Italy facilitated the transfer of old age survivor’s insurance (AHV) and disability insurance (IV) to Italy and prescribed mandatory health insurance for Italian workers. However, discrimination persisted and affected many seasonal and short-term residents. This was especially the case with voluntary insurance schemes. Seasonal workers were thus afforded no protection against unemployment and had limited access to occupational old age provision.

Literatur / Bibliographie / Bibliografia / References: Arlettaz Gérald, Arlettaz Silvia (2006), L’Etat social national et le problème de l’intégration des étrangers 1890 – 1925, Studien und Quellen, 31, 191–217; Gees Thomas (2006), Die Schweiz im Europäisierungsprozess. Wirtschafts- und gesellschaftspolitische Konzepte am Beispiel der Arbeitsmigrations-, Agrar- und Wissenschaftspolitik, Zürich; Mahnig Hans (ed.), Histoire de la politique de migration, d’asile et d’integration en Suisse depuis 1948, Zürich.

(12/2014)

In 1952, the Swiss delegates to the 35th International Labour Conference in Geneva approved Convention 102 on minimum standards in social security. The International Labour Conference constituted the main body of the International Labour Organization (ILO) founded in 1919. Following the dissolution of the League of Nations, the ILO became a special organization of the United Nations (UN) in 1945. The tripartite allocation of national delegations consisting of representatives of government, employees and employers was retained for the regular conferences. Although Switzerland was not a member of the UN at the time, it remained a member of the ILO in 1945.

The ILO was based on the concept that the cooperation of employers, unions and the state formed an essential prerequisite for a lasting peace in industrial relations. It was therefore committed to harmonizing the social policies of member states. Efforts to define minimum standards for social security began in 1948. Convention 102 was passed in June 1952. It stipulated standards for nine insurance domains (medical provision, old age, disability and maternity protection etc.). Adherence to these standards was examined according to statistical criteria (such as regarding the number of people entitled to benefits and the level of the benefits).

Though the Confederation delegates agreed to the convention, its ratification proved problematic for Switzerland. The Federal Council maintained that the country only fulfilled the requirements in the area of accident insurance. Disability insurance had not yet been introduced and AHV pensions were set too low. The Federal Council, however, denied that this meant there was insufficient ‘social protection’ in the country. In fact, it argued the ‘new international instrument’ failed to take into account the ‘specific circumstances of Switzerland’. It was not until 1977 that Switzerland finally ratified the first parts of Convention 102, with the exception of the section governing daily sickness allowance – which remains to this day beyond the scope of Swiss social insurance law. Ratification was therefore delayed until after the establishment of disability insurance (IV) in 1960, the important reforms of old age provision in 1972 and the implementation of family allowances at the cantonal level.

Literatur / Bibliographie / Bibliografia / References: Kott Sandrine, Droux Joëlle (2013), Globalizing social rights. The International Labour Organization and beyond, Basingstoke; Kneubühler Helen Ursula (1982), Die Schweiz als Mitglied der Internationalen Arbeitsorganisation, Bern.

(12/2014)

Chancellor Adenauer himself initiated the pension reform of 1957. According to official proclamations, it sought to establish a new ‘intergenerational contract’ and trigger a process of integration in the young republic. The reform was also aimed at solving the problems caused by the transfer of former social insurance practices into the post-war order.

Despite various attempts at comprehensive basic provision in line with the Beveridge plan, Bismarck’s system of social insurance that was differentiated benefits among categories of policyholders was retained after the Second World War. Following currency reform in 1948, the system was selectively adjusted to include the reintroduction of certain elements of self-administration and the granting of pension supplements. Soon, however, survivor, widow and orphan pensions could no longer keep pace with the rising wages of the post-war boom. In 1955, a report indicated that old age pensions only covered 30 percent of the average wage and many pensioners were living on the breadline.

Adenauer pushed through the pension reform despite opposition from his finance and economy ministers, who were particularly fearful of increasing inflation. On the one hand, the reform included a shift from funded to pay-as-you-go pensions, a system similar to the one introduced for the Swiss old age and survivors’ insurance (AHV) in 1947. Consequently, social insurance disbursed pension benefits financed by payroll contributions paid by future pension recipients rather than by the investment returns of pension reserves. Moreover, the reform provided for ‘dynamic pensions’ that were to be continually adjusted according to general price and wage indices. For German pensioners, this entailed an immediate pension increase of 60 to 70 percent. This enabled them to receive a share of the postwar ‘economic miracle’.

Literatur / Bibliographie / Bibliografia / References: Schulz Günther (ed.) (2005), 1949–1957: Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Bewältigung der Kriegsfolgen, Rückkehr zur sozialpolitischen Normalität (Geschichte der Sozialpolitik in Deutschland seit 1945, Band 3), Baden-Baden; Metzler Gabriele (2003): Der deutsche Sozialstaat. Vom bismarckschen Erfolgsmodell zum Pflegefall, Stuttgart; Stolleis Michael (2003), Geschichte des Sozialrechts in Deutschland, Stuttgart.

(12/2014)

Parliament passed the Disability Insurance Act (IV) in June 1959. Until then, only a portion of workers were affiliated to accident insurance, or were members of pension funds or cantonal insurance schemes that covered them against the risk of disability. In 1925, the establishment of disability insurance was deferred – allegedly to enable a swifter implementation of old age and survivors’ insurance. Consequently, the Confederation only provided modest contributions to institutions dedicated to people with disabilities and charitable organizations such as Pro Infirmis. Many people with disabilities were therefore dependent on social welfare or charity. Disability insurance returned to the political agenda at the beginning of the 1950s. Several parliamentary proposals and two popular initiatives launched by the Swiss Workers Party and the Social Democratic Party also called for its introduction. In 1955 the Federal Council set up an expert commission and published a bill in the autumn of 1958. The bill was swiftly passed by Parliament, allowing the Disability Insurance Act to enter into force on 1st January 1960 without having to face a referendum campaign.

The AHV (old age and survivors’ insurance) served as a blueprint for disability insurance. Its pay-as-you-go system and benefits were adopted directly for the IV. Consequently, the first disability insurance pensions remained far below the subsistence level. From the very beginning, the Disability Insurance Act had at its core the principle of ‘re-integration instead of benefits’: The insurance not only offered cash benefits, but also provided for medical and occupational measures such as vocational guidance or job placement, as well as special educational measures and the provision of assistive devices like wheelchairs or hearing aids. In contrast to British and German legislation, the Disability Insurance Act did not impose quotas on private firms for employing people with disabilities; at the end of the 1950s, the ongoing shortage of labor was expected to create sufficient incentives.

Literatur / Bibliographie / Bibliografia / References: Germann Urs (2008), Eingliederung vor Rente. Behindertenpolitische Weichenstellungen und die Einführung der schweizerischen Invalidenversicherung, Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Geschichte, 58, 178–197; Lengwiler Martin (2007a), Im Schatten der Arbeitslosen- und Altersversicherung. Systeme der staatlichen Invaliditätsversicherung nach 1945 im europaïschen Vergleich, Archiv für Sozialgeschichte, 47, 325–348.

(12/2014)

The proportion of men and women dependent on welfare fell considerably from 1960 onwards. This was a result of the introduction of old age and survivors’ insurance (1948) and disability insurance (1960) – not to mention full employment and wage growth during the postwar boom. The burden faced by communal welfare offices in particular was greatly reduced. At the same time, social workers increasingly encountered difficult social situations. Poverty in welfare society of abundance society was often interpreted as a sign of individual adaptation difficulties.