Unternavigation

Edmund Schulthess

The liberal politician Edmund Schulthess (1868-1944) was a member of the Federal Council from 1912 to 1935. In 1925, as head of the Federal Department of Economic Affairs, he was involved in laying the constitutional groundwork for old age, survivors’ and disability insurance as well as for the first draft for a national old age and survivors’ insurance (AHV) – which failed at the ballot box in 1931.

Edmund Schulthess grew up in the rural areas of the canton Aargau. After completing his law degree, marrying his wife and starting a family, he started work as a business lawyer in Brugg. He specialised in financial and labour law, and was a board member of companies the electricity industry and the banking sector. He soon became close friends with Walter Boveri, the founder of Brown Boveri & Cie. (presently Asea Brown Boveri ABB) as well as Ernst Laur, director of the Swiss Farmers’ Association. Schulthess was politically affiliated with the liberal democratic party (FDP). In 1893, he was elected cantonal councillor for Aargau and Council of States in 1905 with the backing of the Farmers’ Party and the Catholic conservatives. In 1912, he was elected to the Federal Council, where he took on the Federal Department of Economic Affairs. Schulthess held the position of federal president four times before resigning in 1935.

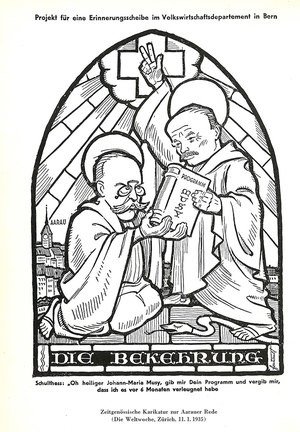

Due to his liberal affiliations, Schulthess felt a strong obligation to serve business interests. Yet, he also advocated compromises for the working class and recognised the need for state intervention to stabilise supply and demand. During his long tenure as head of the Federal Department of Economic Affairs, he shaped the economic and social policy during the war and the interwar period. From 1917 onwards, he oversaw the wartime economy that had been until then insufficiently organized. In the interwar period, however, Schulthess’ economic policy faced opposition from both the political left and right. Both a revision of the labour law (1924), which included longer working hours, as well as a proposal for a federal monopoly on grain (1926) were rejected by voters. It was not until the second attempt in 1929 that Schulthess was able to gain a majority for a new grain law. Within the Federal Council, there were growing tensions between Schulthess and his Catholic-conservative colleague Jean-Marie Musy, who advocated a restrictive financial policy. The tensions came to a head shortly before the referendum on the AHV bill in late 1931. However, once the Great Depression hit in 1932, Schulthess also called for wage and price reductions and the depreciation of the Swiss franc. Nonetheless, he was in line with the bourgeois parties in rejecting the crisis initiative pushed by social democrats and unions demanding anti-cyclical economic policy.

Schulthess already seemed weary of office in 1928 and stepped in 1935. Following his resignation, he took on several management mandates and became the chairman of the newly founded Federal Banking Commission. Furthermore, he led Switzerland’s government delegation at the International Labour Conference. In February 1937, Schulthess met with the German Reich Chancellor Adolf Hitler in Berlin in his capacity as a private individual, yet in consultation with the Federal Council. Hitler assured him that Germany would respect Swiss neutrality in the event of a future European conflict.

In his role as minister of economic affairs, Schulthess was responsible for many aspects of social security. For instance, the wartime rationing, control and assistance measures taken by the Federal Council towards the end of the First World War under the aegis of Schulthess were strongly motivated by social policy. They sought to improve provision to the population and alleviate social tension. After the war and the general strike, the Federal Department of Economic Affairs prepared a proposal for improving labour relations; however, this proposal was rejected by a close majority of voters in 1920. The federal department was likewise responsible for job creation in the post-war period and the first Federal Act on Unemployment Insurance of 1924.

In particular, Schulthess’ remit included the Federal Social Insurance Office (BSV) and hence the responsibility of preparing an old age, survivors’ and disability insurance which had come to a halt as a result of the First World War. Schulthess held a firm conviction for the principles of solidarity and insurance, as well as the need for swift execution in policy; he thus proposed a new bill in 1919. He astutely exploited the new acceptance for social policy which was even shared by the bourgeois camp in the immediate aftermath of the war. After tense negotiations primarily concerning the financing of the proposed social security system, voters and Parliament passed the proposal for a new constitutional article on 6th December 1925. The Confederation was thus authorised to introduce old age and survivors’ insurance (AHV). Later, the same was achieved with regard to disability insurance. To set out the details, Schulthess’ department then prepared a legislative proposal, which was presented to Parliament in 1929 and to voters in 1931, following a referendum campaign.

The AHV bill of 1931 was minimal and designed as a supplement to existing occupational provision. It contained an insurance obligation, individual premiums, standard pensions and allowances for those in need. The division of tasks between state and occupational provision was especially controversial. Exponents of the insurance industry pushed for as limited a state pension as possible to preserve market opportunities for life insurers offering supplementary insurance. In addition, there was pressure on federal finances channelled effectively by Musy. Although Schulthess’ proposal passed through Parliament largely unscathed and was backed by a large majority, a referendum was called by an ragtag alliance of liberal conservatives from western Switzerland, farmers and followers of Catholic social doctrine. The latter presented an alternative welfare initiative, which envisaged an old age assistance scheme based on means tests and preserving cantonal autonomy. As it had been the case thirty years previously with the ‘Lex Forrer’, the first AHV bill foundered on 6th December 1931. Two thirds of voters rejected the proposal; with voter participation amounting to around 80 percent. The introduction of a tobacco tax to finance the AHV was rejected as well. In this case, it was the Communist Party of Switzerland – whose exponents named the AHV bill ‘beggar’s soup’ – which had called the referendum. The fact that the economic crisis was taking hold in Switzerland at the time evidently made it difficult to convince voters even of a modest expansion of social provision.

The failure of the AHV bill represented a significant personal setback for Schulthess. The Neue Zürcher Zeitung referred to the outcome as a ‘catastrophic defeat’ for the welfare state. Nevertheless, Parliament reappointed Schulthess as federal councillor with an excellent result only one week later, while his rival Musy had to make do with a significantly inferior result.

Literatur / Bibliographie / Bibliografia / References: Böschenstein Hermann (1966), Bundesrat Edmund Schulthess. Krieg und Krisen, Bern; Altermatt Urs (1991), Die Schweizer Bundesräte. Ein biografisches Lexikon, Zürich.

(12/2014)