Unternavigation

The Center

Since its foundation at the beginning of the 20th century, the Center (founded in 1912 as the Swiss Conservative People's Party) had been defined by Christian social tendencies and committed to social policy. These tendencies became particularly evident in its parliamentary activity as well as in Christian associations and trade unions, which echoed the party’s dedication to family protection.

In political terms, the Catholic Conservatives began organising in opposition to secular and liberal worldviews in the first half of the 19th century. Having conceded defeat to the Free Democrats in 1848, the Catholic Conservative elite represented a political minority at the federal level. It was not until 1891 that the Catholic Conservatives were able to gain their first seat in the Federal Council and a second in 1919 as part of the consolidation of the conservative alliance against the workers’ movement. This integration was accompanied by a general rapprochement towards liberal economic policy, although conservative positions were retained particularly on cultural and religious issues.

In 1912, the Catholic Conservatives became organised at the federal level and set up the Swiss Conservative People’s Party, renamed the Conservative Christian Social People’s Party in 1957 and then the Christian Democratic People’s Party (CVP) in 1970. From 1920 to the end of the 1980s, the party represented between a fifth and a quarter of the electorate and held around a quarter of the seats in the National Council and 40 percent of the seats in the Council of States. Thereafter, the share of its voters eroded and, in 2011, the CVP only represented 12 percent of voters and held 28 seats in the National Council. The CVP lost one of its two seats in the Federal Council to the Swiss People’s Party (SVP) in 2003.

In social policy, the conservative wing of the party played a substantial role in delaying the introduction of social insurance – in particular by rejecting Lex Forrer in 1900. That said, Christian social doctrine led the party to promote certain forms of social security that were often not entirely different from socialist initiatives. In 1891, Pope Leo XIII’s encyclical Rerum Novarum provided the first official theoretical foundation to the Christian social policy alignment. While opposing socialism, it nevertheless promoted workers’ mutualism and advocated social measures by the state for the lower classes. Numerous Christian societies emerged, both in the area of culture as well as in cooperative workers’ assistance. They supported the political organisation of the Catholic wing and attempted to create a countermovement against the rising workers’ movement that was considered a threat to Catholicism. The creation of the Central Association of Swiss Christian Social Organisations (1903) and the Christian Social Federation of Trade Unions (1907) reinforced this Christian social milieu. The Christian unions as well as those affiliated with the Swiss Federation of Trade Unions, founded their own provident funds, notably in the areas of illness, accident and unemployment.

The ideological solidarity between these various Catholic organisations crumbled after the Second World War; a gulf emerged between the church and the Catholic-conservative party. The relatively close unity of the Catholic political camp now offered space for diversity of opinion – a process further bolstered by urbanisation and the massive immigration of Catholic workers from southern Europe. At the grassroots level, the social wing gained traction over the conservatives.

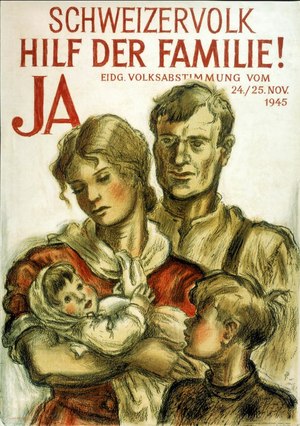

In relation to the welfare state, the CVP was particularly committed to family policy. The party submitted the popular initiative ‘Protecting the Family’ in 1942. The initiative was withdrawn in favour of a counterproposal that enshrined maternity insurance and family allowances in the constitution in 1945. By launching this initiative, the Catholic Conservatives campaigned for a societal model influenced by the church’s social doctrine; it emphasised the ‘natural unit’ of the traditional family and the concept of different social roles for men and women. The initiative was also presented as an alternative to the AHV advocated by the left and the FDP. By 1931, Catholic-Conservative groups had already began to counter the project for old age insurance, appealing to the argument of maintaining personal responsibility and private provision.

In the second half of the 20th century, the CVP supported the introduction of disability insurance (1960) and compulsory unemployment insurance (1976). The party advocated the introduction of compulsory health insurance, although it developed a critical stance towards expanding social expenditures in the 1990s. Considering that demographic ageing was putting under stress the financing basis of social insurance, a majority of the CVP backed reforms seeking a reduction of benefits in certain social policy areas. This new policy direction, however, did not prevent party members from campaigning for maternity leave – introduced in 2004 – or for the harmonisation of family allowances.

Even after merging with the Conservative Democratic Party (BDP) and renaming itself The Centre, the party maintained an ambivalent stance toward the expansion of social benefits. For instance, it campaigned against the 2024 initiative for a 13th AHV pension, which voters clearly approved, while supporting the paternity leave introduced in 2021 (renamed leave for the other parent in 2024).

Literatur / Bibliographie / Bibliografia / References: Altermatt Urs (1993), Schweizer Katholizismus in Umbruch, 1945-1990, Fribourg; Altermatt Urs (1994), Le catholicisme au défi de la modernité. L’histoire sociale des catholiques suisses aux XIXe et XXe siècles, Lausanne; Schorderet Pierre-Antoine (2007), Crise ou chrysanthèmes? Le Parti démocrate-chrétien et le catholicisme politique en Suisse (XIXe-XXIe siècles), Traverse. Revue d’histoire, 1, 82-94.

(08/2025)