Unternavigation

Women’s Movements

Women’s rights advocates have played an active role in debates surrounding the expansion of social security in Switzerland since the beginning. They advocated the creation of social insurances, called for specific regulations to protect female workers – in the event of maternity for instance – and criticized the discriminatory nature of certain aspects of social legislation.

Women’s rights associations emerged in many Swiss cities at the end of the 19th century. They demanded better working conditions as well as civil and political rights. These associations were mainly composed of bourgeois women who had already been active in other women’s organisations in welfare and education. The first Congress for Women’s Interests in 1896 led to the foundation of the Federation of Swiss Women’s Associations (BSF). This federation proved highly effective in uniting women’s groups with very different concerns: voting rights activists, professional associations such as for teachers or midwives, as well as charities. The female activists who emerged from the workers’ movement founded their own organisations, including the Swiss Association of Women Workers that remained separate from the BSF.

Although the right to vote represented the main demand of this first wave of feminism, social policy issues were also on the discussion agenda. BSF member Marguerite Gourd gave a speech on social insurances at the congress of 1896. Thereafter the congress adopted several demands: the introduction of maternity insurance, the immediate creation of compulsory health insurance for children and eventually the whole population, as well as the creation of old age, disability and survivors’ insurance. Subsequently, the BSF paid close attention to federal policy in relation to social security and appointed a commission of female experts in the field of social insurance. Some of these experts were among the first women to take on a leading or expert role in the federal administration.

The activists who emerged from the workers’ movement were likewise interested in social policy and the protection of female workers. After a highly militant period in the 1920s, socialist and communist women returned to a more traditional perception of women's roles during the economic crisis decade; this model closely reflected the ideal of bourgeois women and upheld the roles of housewives and mothers. These activists distanced themselves once again from the «housewife» ideology in the 1960s and launched a new debate on women’s work. Due to the influence of the women’s liberation movement of the 1970s in particular, trade union and left-wing woman activists set a new course and adopted a more open approach to the issue of equality. OFRA, a feminist and Marxist group, emerged in the context of the emergence of other progressive organizations in Switzerland (e.g., POCH), and eventually became the most important group in the FBB. At its founding congress, OFRA members decided to launch a popular initiative focused on maternity protection. As was the case in other European countries, these women’s groups called into question the social roles ascribed to men and women. Although the main demands focused on abortion rights, contraception and sexual self-determination, social policy issues were also addressed.

Despite discrepancies within the women’s movement, the protection of women in maternity, widowhood, illness and old age lay at the heart of feminist demands throughout the 20th century.

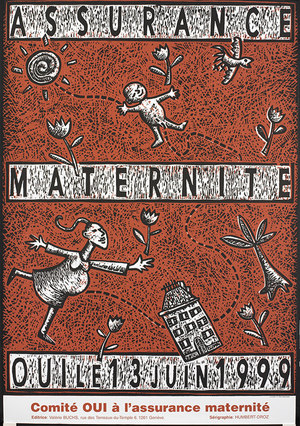

The Campaign for Maternity Insurance

In 1902, the introduction of maternity benefits figured among the demands made by the Swiss Association of Women Workers. Margarethe Faas-Hardegger, the first secretary of the Swiss Federation of Trade Unions also spoke in favor of the idea. Backed by various women workers’ associations, the BSF submitted in 1904 a petition calling on the Federal Council to introduce a maternity insurance. The associations also demanded continued pay during eight weeks in case of maternity (of which at least six of which after birth), during which work was prohibited in accordance with the Federal Factory Act of 1877. The petitioners sought to prevent pregnant women or new mothers from having to accept wage cuts or being forced to forego maternity leave, which would endanger their health and that of their baby. In 1927, a national socialist women’s conference called for the introduction of maternity leave and dismissal protection in line with the ‘Convention on the Employment of Women Before and After Childbirth’ of the International Labour Organization (ILO) which had been passed in 1919 at the International Labour Conference in Washington.

Despite the large consensus among women activists on this issue and the famous survey by Margarita Schwarz-Gagg demonstrating the low extent of the protection of mothers in 1938, no significant progress was made in this area prior to the end of the Second World War. The constitutional obligation to introduce maternity insurance was passed in 1945, as a result of Catholic conservatives’ efforts to protect the family unit. Over the course of the following decade, the sharing of costs involved in the medical care of new mothers improved, but neither health insurance nor various revisions to labor law led to an insurance scheme for loss of income. Renewed initiatives for maternity insurance emerged with the women’s movement of the 1970s, albeit without any success. In 1984, the popular initiative ‘For the Effective Protection of Motherhood’ launched by the women’s movement, left-wing parties and trade unions was rejected by 84 per cent of voters. The demand continued to be a key women’s issue, particularly during the national women’s strike on 14th June 1991 on the tenth anniversary of the constitutional article declaring the equality of men and women. In 1995, the 50th anniversary of the constitutional article on maternity insurance was commemorated with a national women’s rally calling for the article’s immediate implementation. Following numerous other initiatives and another referendum defeat in 1999, the Swiss electorate finally accepted the introduction of a federal maternity leave in 2004. More recent demands by the women’s movement include the introduction of a paternity leave and parental leave, alongside improved benefits during maternity leave. Another women’s strike was held on 14th June 2011 to raise awareness to these issues.

Greater Protection for Widows and Retired Women

The protection of retired women and particularly that of widows was a key issue for women’s organisations from the onset of the 20th century. During the Congress for Women’s Interests in 1896, attendees already called for the creation of compulsory old age, disability and widows’ insurance.

Representatives of the BSF became involved in the expert commission’s work to anchor the idea of an AHV in the constitution (1925) and to prepare the first federal act on old age insurance, which was rejected at the ballot box in 1931. However, women activists had to fight for a place on the commission outlining the AHV bill of 1948 and, albeit unsuccessfully, advocated that married women should be entitled to an individual pension. Besides increases to minimum pensions, feminists and union activists also demanded an improvement to the situation of married women, as well as divorced women and widows. In 1997, the tenth AHV revision that was passed under Ruth Dreifuss’ tenure as federal councillor satisfied this demand to some extent by introducing an individual pension system less dependent on marital status, remunerations for child-raising tasks, better widows’ pensions as well as splitting (when calculating pensions, earnings achieved by married couples during the marriage were split up, half of which were credited to the wife and half to the husband). Yet, the 1997 revision also contained a gradual increase to retirement age from 62 to 64 years, which went against the demands for a reduction in retirement age put forward by feminists from the workers’ movement.

In 1948, the retirement age had been set at 65 years for all, but it was subsequently reduced to 63 for women in 1957 and to 62 in 1964. The authorities justified this reduction on the basis of the lower pensions women received. The Federal Council also held the view that women were forced to exit the workforce earlier in life due to a more rapid decline in physical strength. An eleventh AHV revision that envisioned a retirement at 65 years for both men and women failed in a 2004 referendum, particularly due to the mobilization of women as well as feminist active in trade unions. The activists rejected what they considered would entail an increase in working hours, since they were advocating precisely the opposite: working hours ought to be cut so that unpaid family work – typically performed by women – would be more recognized and shared. During this campaign, feminists also pointed out that wage inequalities, part-time work and the years spent raising children were resulted in below-average old age pensions for women.

Women and Health Insurance

In 1911, the BSF advocated compulsory coverage as part of the expert commission on health insurance. The organization later criticized the higher premiums that women had to pay (these were justified with the medical services associated with childbirth), as well as the restrictions some health funds enforced in the admission of married women. In the 1930s, the Federal Council allowed health funds to set premiums up to 25 percent higher for women than men. The BSF criticized this practice of considering women as risk factors for funds, particularly as it compelled them to bear the costs of childbirth and childcare alone.

Women’s organisations advocated a better approach to sharing the medical costs related to pregnancy and childbirth. Care benefits were notably expanded in the 1964 revision, but since there was no compulsory insurance until 1994, some women were still left without cover from a health fund.

In addition, maternity insurance had not been introduced at the time. Feminist activists thus demanded that health insurance provide compensation for loss of income for new mothers throughout the whole 20th century. Just like earlier legislation, the KVG of 1994 included the option of supplementary insurance against loss of income due to maternity, but the insurance remained voluntary. Although differences in premiums between the sexes were not permitted in basic insurance, this was not the case for supplementary insurance.

Protection of Unemployed Women

During the early 1920s crisis, the BSF protested against a plan from the federal authorities that envisioned denying benefits to unemployed women in order to force them to accept domestic work. During the crisis of the 1930s and the Second World War, the BSF and women activists from the workers’ movement had to fight back attacks against the work of married women as well as challenges to the compensation entitlement of unemployed married women.

BSF activists, feminists from the workers’ movement and women committed to the women’s liberation movement paid close attention to projects leading to the introduction of compulsory unemployment insurance during the crisis of the 1970s. These efforts ultimately resulted in the implementation of the Federal Act on Compulsory Unemployment Insurance and Insolvency Compensation (AVIG) of 1982. The activists demanded and achieved greater protection for unemployed pregnant women and new mothers, as well as improved recognition of part-time work in insurance. In 1995, a ‘child-rearing period’ in unemployment insurance was introduced in response to feminist demands for the recognition of time spent raising children. The third AVIG revision in 2002 changed this provision and was subsequently met with criticism from women’s organisations. Time spent on child rearing was now no longer considered equivalent to gainful work (and thus as a contribution period). The act only extended the deadline for submitting evidence of a year of contribution in Switzerland from two to four years. In the case of the fourth AVIG revision in 2011, debates mainly focused on the younger generations affected by the new benefit rules. However, a number of feminists involved in trade unions emphasized the negative consequences of higher contribution requirements and of reduced benefits for people exempt from contributions.

Literatur / Bibliographie / Bibliografia / References: Despland Béatrice (1992), Femmes et assurances sociales, Lausanne; Luchsinger Christine (1995), Solidarität, Selbständigkeit, Bedürftigkeit. Der schwierige Weg zu einer Gleichberechtigung der Geschlechter in der AHV 1939-1980, Zurich,; Mesmer Beatrix (2007), Staatsbürgerinnen ohne Stimmrecht. Die Politik des schweizerischen Frauenverbände 1914-1971, Zurich ; Redolfi Silke (2000), Frauen bauen Staat. 100 ans de l’Alliance de sociétés féminines suisses (1900-2000), Zurich ; Studer Brigitte (1998), Der Sozialstaat aus der Geschlechterperspektive. Theorien, Fragestellungen und historische Entwicklung in der Schweiz, In Studer B., Wecker R. et Ziegler B., Les femmes et l'Etat, Schwabe, Basel, 184-208 ; Togni Carola (2013), Le genre du chômage. Assurance chômage et division sexuée du travail en Suisse (1924-1982), Berne ; Wecker Regina (2009), Ungleiche Sicherheiten. Das Ringen um Gleichstellung in den Sozialversicherungen, In Schweizerischer Verband für Frauenrechte, Der Kampf um gleiche Rechte, Basel.

(12/2017)