Unternavigation

Social Security as seen from an International Perspective

The history of the Swiss welfare state is intertwined with international organizations committed to social policy. They exerted considerable influence on Switzerland, albeit often in an indirect and informal manner.

Being a neutral country, Switzerland was a favored location for international organizations such as the League of Nations or various special organizations active under the United Nations umbrella. It joined the League of Nations shortly after its foundation in 1920. Yet, Swiss authorities deferred admission to many other organizations for a long time, including the Council of Europe, the International Monetary Fund or the United Nations. The reasons for this hesitation ranged from concerns about remaining politically neutral, to political isolationism among the bourgeois circles, although Switzerland was at the same time strongly integrated in the world economy.

In the domain of social policy, Switzerland maintained close relations with a number of different international and supranational organizations. These included the International Labor Organization (ILO), the Council of Europe, the World Health Organization (WHO), the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) as well as the European Union and its predecessors (the European Economic Community EEC, and the European Community EC). Moreover, Switzerland has signed 44 bilateral intergovernmental social law agreements.

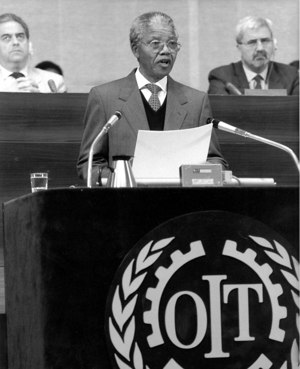

The ILO was the most important international organization for social security issues until the 1970s. It was established in 1919 as an institution of the League of Nations and has been a special organization of the United Nations since 1946. It is composed of a permanent secretariat (the International Labor Office), an administrative council and a general assembly that convenes each year at the International Labor Conference. The administrative council and general assembly are made up of a tripartite allocation of government, employer and employee representatives. This corporatist organization aimed to spread the idea of social peace and social security from industrialized countries to the rest of the world. The social and labor-law resolutions of the ILO constitute the most important instruments to reach this objective. The Labor Conference passes conventions and recommendations relating to matters of social security, as well as generally with regard to human rights issues, social inequality and societal development. The ILO resolutions enter into force once they are ratified by the member states.

Switzerland figured among the founding members of the ILO and had already been the main seat of its most important predecessor organization, the International Labor Office founded in Basel in 1901. However, Switzerland has had an ambivalent relationship with the ILO. Although Swiss social insurance figures such as Suva director Alfred Tzaut or AHV expert Ernst Kaiser took on leading roles in expert commissions in the ILO or the ILO-related International Association for Social Security (IVSS), Switzerland only ratified the ILO’s conventions and recommendations with reluctance. In the eight decades since the founding of the ILO (1919-2000), the Swiss Confederation only adopted around 30 percent of the ILO resolutions (56 of 183). Considering only the resolutions concerning social security and workers’ protection, Switzerland adopted 14 of 40 conventions (i.e. around a third between 1919 and 2000). The Swiss authorities held a reluctant stance towards the ILO resolutions due in part to differing conceptions of social security. Following the Second World War, the ILO favored integrated models of social security with a state benefit system. Whereas in 1950, the Swiss state only had a compulsory accident insurance (Suva) as well as a minimalist old age and survivors’ insurance (AHV), supplemented by relatively strong private provision systems such as occupational pension funds or health funds. State disability insurance only came about in 1960, compulsory unemployment insurance in 1977, compulsory health insurance in 1996 and state maternity insurance in 2005. Against this backdrop, the Federal Council therefore only had a limited capacity to pursue the Philadelphia Declaration passed by the ILO in 1944, which became part of the revised constitution of the organization in 1946 and contained core requirements of social policy. The Swiss authorities considered themselves incapable of ratifying the most important ILO convention of the post-war period, the 1952 convention for minimum standards in social security. The convention stipulated that signatory states had to guarantee minimum standards in social security for three of nine forms of social insurance. It was not until 1977 – after introducing compulsory unemployment insurance – that Switzerland satisfied this condition and was able to join the convention.

Switzerland’s relationship with the Council of Europe was similarly contradictory with respect to social policy. Switzerland was among the more active countries in the Council of Europe following its admission in 1963, including matters of human rights or democratic rights. Swiss authorities also adopted a number of social policy conventions, in particular the European Convention on Social Security (1964), but did not sign the European Social Charter (1961) or various other conventions on old age provision or health insurance. A major obstacle for adopting the Social Charter was the seasonal workers’ statute in migration policy, which denied affected immigrants’ basic social rights.

Switzerland has been a founding member of the OECD since 1961. Its relationship with the OECD has been somewhat less fraught with difficulties, particularly as the OECD is not a legislative body but instead seeks to exert influence on member states through international consultation and advisory committees as well as research and publication activities such as statistical comparative studies. The relations between Swiss authorities and the European Union (EU) and its predecessors have also been close since the 1960s, even though Switzerland is not a member state. Early agreements with the EEC or the EC primarily concerned cross-border insurance coverage for migrants. In 1999, the signing of the Agreement on the Free Movement of Persons in connection with bilateral treaties brought about broader harmonization of social policy between Switzerland and the European Union. Switzerland’s closer alignment with the EU, however, indirectly created new inequalities, particularly between the comparatively generous treatment of EU citizens and the more restrictive treatment of immigrants from countries outside the EU.

Literatur / Bibliographie / Bibliografia / References: Gees, Thomas (2006), Die Schweiz im Europäisierungsprozess. Wirtschafts- und gesellschaftspolitische Konzepte am Beispiel der Arbeitsmigrations-, Agrar- und Wissenschaftspolitik 1947-1974. Zürich; Martin Senti (2000), Die Schweiz in der ILO, Bern; Lengwiler, Martin, Expert networks and the ILO in 20th century accident insurance, in: Kott, Sandrine, Droux, Joëlle (2013), Globalizing social rights. The ILO and beyond, London, S. 32-46.

(12/2014)