Unternavigation

Accident and Military Insurance

Workers had a right to compensation for work related accidents and illnesses since 1877. Before compulsory accident insurance was introduced, workers had to assert this right themselves. Insured workers received an automatic entitlement to compensation with the establishment of Suva in 1918. However, during the interwar period, Suva was hesitant in enforcing this entitlement.

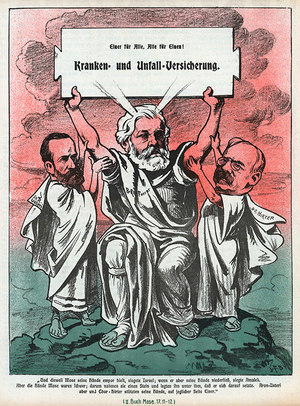

Concerns about the physical dangers of industrial work (work and occupational accidents) preoccupied broad swathes of the general public in the 19th century, particularly the proponents of social reform. The Factory Act of 1877 brought about the basic principle that business owners were liable to injured workers, when the accident related to working conditions and was not caused by negligence on the part of the injured. In disputed cases, when a business owner denied that working conditions had caused the accident, the injured would have to take their case to court in assert their claim. Yet, many victims of accidents were unable to afford such legal action. Criticism of liability law become more urgent in the 1880s after Germany introduced compulsory accident insurance. Soon, there were calls to introduce a similar system in Switzerland. According to the insurance model, injured parties had an automatic claim to compensation; all they had to do was report the occupational accident. The insured workers – or rather the unions – were also involved in the administration of accident insurance.

Members of the military were the first to benefit from compulsory accident insurance in Switzerland. The Confederation was obliged to provide this insurance cover as the employer. In 1887, the Swiss army had already entered into a contract with the Zurich accident insurance company to provide accident insurance to military personnel – though only on a voluntary basis. The Confederation began assuming the costs of accident insurance in 1895 and made it mandatory for the entire military. Although the general health and accident insurance bill – including an insurance obligation for industrial workers – failed at the ballot in 1900, the accident insurance for military personnel was supplemented by a compulsory health insurance in 1901. This protection was considered a patriotic imperative and was politically undisputed.

Once the Swiss Institute for Accident Insurance (Suva) was established in 1918, workers in the industrial sector were admitted to the compulsory accident insurance scheme. On the one hand, the insurance principle gave policyholders the relief they had been hoping for. Whenever occupational accidents occurred, they would generally not have to take any special action to obtain compensation. On the other hand, Suva strove to uphold its public image as a frugal institution during the interwar period for political reasons. In the 1920s, Suva warned that social insurances would ‘soften’ policyholders and cause dependency. Suva was thus restrictive with respect to granting cover for occupational illnesses or providing disability pensions. In the first instance, Suva generally refused any claims relating to illnesses or health problems, when it was not completely obvious that they were work-related. The institute often accused its policyholders of improper intent, such as pretence or chronic hyperbole (‘pension neurosis’). Whenever Suva approved a disability pension, the institution would seek to arrange speedy rehabilitation and re-integration measures for the policyholders; it also established its own medical centres for this purpose. For a long time, Suva denied cover for various ‘extraordinary risks’ within the context of leisure risks, such as car and motorcycle use (provided they were not associated with an occupation) to hunting and various disciplines of top-class sport. These risks were only added to accident insurance gradually (car use in 1941 and motorcycle use in 1967). Suva has not only expanded the insured risks since the interwar period and especially after 1945, but also the scope of sectors covered by insurance. Comprehensive insurance cover was provided to the service sector in 1964 and the agricultural sector in 1984.

Literatur / Bibliographie / Bibliografia / References: Lengwiler, Martin (2006), Risikopolitik im Sozialstaat. Die schweizerische Unfallversicherung 1870-1970, Köln; Degen, Bernard (1997), Haftpflicht bedeutet den Streit, Versicherung den Frieden: Staat und Gruppeninteressen in den frühen Debatten um die schweizerische Sozialversicherung. In: Siegenthaler, Hansjörg (Hg.). Wissenschaft und Wohlfahrt: Moderne Wissenschaft und ihre Träger in der Formation des schweizerischen Wohlfahrtsstaates während der zweiten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts. Zürich, S. 137–154.

(12/2015)