Unternavigation

Old Age Provision

The question of how society can guarantee a reasonable level of income for older people was a topic of frequent debate in the 20th century. Due to the substantial resources that are used to this end and the number of people dependent upon it, old age provision remains one of the most controversial topics in providing social security to this day.

Old Age Provision before 1914

During the second half of the 19th century, Swiss society experienced a first phase of demographic aging. The place older people held in society had to be reconsidered. At that time, the issue of old age pensions was closely associated with the risks of disability and illness since these disproportionately affected older people and their access to sufficient income remained uncertain. The question how the elderly could be guaranteed a decent life therefore became a fundamental problem for society. Prior to 1914, only a handful of pension plans existed in public administrations and a few innovative companies. Some cantons introduced voluntary old age savings, including Vaud and Neuchâtel in 1907. Charitable institutions also provided limited support for the destitute or disabled elderly. However, most older people continued to work until almost the end of their lives, as they could only expect aid for the truly needy or from their families. Retirement with a set income simply did not exist as a distinct phase of life.

Fundamental questions regarding old age pension became the subject of debate in 1890. All agreed that action was needed to support older people, but the different parameters of old age provision gave rise to discussion: should old age insurance be introduced, or should assistance benefits be limited to specific cases, thereby motivating individuals to provide for themselves by saving for their old age? Who should organize this support: the Confederation, cantons, firms or private individuals? Could such a programme be funded by taxes, wage deductions or income from savings? How high should the benefit amounts be and how could the system be sustained in the long term? These questions arose time and again throughout the course of the 20th century and are still relevant in the early 21st century. Nonetheless, old age provision remained a secondary concern between 1890 and 1914 as the debates at the time over social security initially focused on accident and health insurance. After the outbreak of the First World War brought about a temporary interruption in socio-political debate on this issue, old age pensions quickly re-emerged on the political agenda.

The Advent of Occupational Pension Plans and the AHV Project, 1918–1938

After the war, the labor movement urgently called for the creation of an old age, survivors’ and disability insurance – particularly during the general strike of 1918. However, this demand was difficult to realize during the interwar years. The first drafts for a federal old age pension system date back to 1919, but it took until 1925 and the acceptance of a constitutional revision to pave the way for a legislative bill. This project was prepared under the leadership of liberal FDP federal councillor Edmund Schulthess in the second half of the 1920s. In 1929, both chambers of the Federal Assembly approved the proposal for an old age and survivors’ insurance (AHV) – called the Lex Schulthess. Yet, it failed in the referendum launched by conservative groups opposed to social insurance; voters rejected the Lex Schulthess on 7December 1931. This was despite the fact that the proposal had been revised several times between 1918 and 1931. For instance, the envisaged benefits were reduced and a section calling for the introduction of disability insurance was dropped. The biggest political stumbling block came from the proposal to partly fund pensions through taxes; this was met with opposition from middle-class parties opposed to increased intervention by the Confederation. The question whether the future state pension system would cooperate or compete with existing occupational pension plans also triggered fears particularly among employers. The Lex Schulthess thus proposed very limited pensions in order to avoid competing with occupational pension benefits. It was to be financed primarily through wage deductions and monies raised from taxing tobacco and alcohol.

Although the first AHV proposal failed, things looked quite different in the pension funds. Occupational provision enjoyed a first boom immediately following the First World War and remained largely untouched by the controversies surrounding the AHV. Pension plans controlled by individual employers or managed by life insurers were developed in a decentralized manner, spurred on by tax relief and the use of old age provision to control and retain workers. Pension plan representatives held differing opinions about the Lex Schulthess, but its defeat in 1931 left behind a vacuum that proved advantageous to private solutions. It enabled existing plans to further develop without having to fear competition from the government. These various developments – on the one hand the spread of private occupational provision, and on the other the failure of public social insurance – would shape the development of old age provision for years to come. They laid the foundation for the mixed form of old age provision which lasted into the second half of the 20th century.

The AHV as a Once-in-a-century Event 1938–1948

The triumphant yes vote in favor of old age and survivors’ insurance on July 6 1947 (80 percent in favor, and a 79 percent participation rate) was a turning point. Yet, this success was anything but foreseeable at the beginning of the Second World War.

In 1941, existing cantonal old age insurance schemes barely covered five percent of the population. Demographic aging also revealed the inadequacy of existing aid structures and support programs. In 1938, a parliamentary motion by FDP national councillor Arnold Saxer put the issue of a federal AHV back on the agenda. However, in 1939, the focus in social insurance matters was on the income compensation scheme for mobilized soldiers. It was not until 1943 when the tide of war turned in favor of the Allies and a number of social insurance proposals were elaborated internationally (including the British Beveridge Plan) that the AHV rose again to the top of the political agenda. Stimulated by the popularity of the income compensation scheme, several cantonal initiatives as well as the popular initiative ‘For a Secure Old Age’ – which enjoyed broad political support – called for the swift introduction of an AHV. Things then moved at an accelerated pace. In 1944, the FDP member of the Federal Council responsible for the dossier, Walther Stampfli, picked up on the various initiatives and instructed the Federal Social Insurance Office to prepare a draft AHV bill which adopted the structures (equalization funds) and the wage contribution financing system (pay-as-you-go) from the income compensation scheme. In the pay-as-you-go system, current income, which essentially consists of wage-related contributions from insured persons, directly finances the insurance benefits.The bill was accepted by the Federal Assembly at the end of 1946 and triumphed against a referendum launched by the conservative right in July 1947. A number of other European countries also introduced basic pensions after 1945, financed either from wage-dependent contributions or out of taxes.

The success of the AHV can be traced back to the fact that it did not challenge the existing pension schemes. On the contrary, the initial AHV pensions were set low– they amounted to around ten percent of an industrial worker’s wage in 1948 – and served as a stepping-stone for the pension funds that had undergone a further expansionary phase during the Second World War. The pension plans thus once again became a central tenet of employers’ social policy. Although the division of tasks between a minimal AHV and existing pension schemes offering supplementary benefits triggered serious debate among experts, it was not explicitly mentioned in the AHV bill. Indeed, the open nature of the bill was a key objective for Walther Stampfli as well as for the life insurers. The latter would only accept an AHV that guaranteed the independence and further development of private provision.

The Expansion of Old Age Pensions and the Three-Pillar System, 1948–1985

During the decades of growth in the postwar period, public and private old age pension schemes expanded in parallel. The central challenge of this period concerned how to define the boundaries and divide the tasks between the two domains. On the AHV side it, the discussion was how to increase the modest basic pension. Since the 1950s and 1960s, other Western European countries also asked how the modest level of state basic insurance for old-age provision could be increased through supplementary insurance. The measures taken differed from country to country. In France, coverage was not universal, though starting in 1947, supplementary pension schemes would gradually extend it to previously excluded groups such as government workers or farmers. pensions were supplemented with "special regimes" that were differently furnished depending on the sector and company. The basic and supplementary pensions were both financed by the pay-as-you-go method. Germany, Austria and Italy also opted for this method in their supplementary pension schemes. By contrast, the Netherlands and the UK, like Switzerland, opted for pension funds managed either by individual companies or life insurance companies. The pension fund contributions accumulated in the capitalization process were invested in order to be able to finance future pensions. The capitalization process also played a decisive role in the Scandinavian countries, where pension funds were directly controlled by the state.

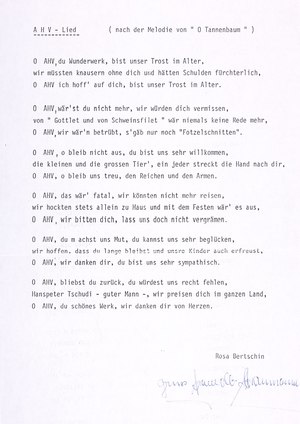

The AHV was revised eight times between 1951 and 1975. These revisions introduced a number of improvements to the benefits (pensions increased from ten percent of the average wage in 1948 to 35 percent in 1975) as well as higher payroll contribution rates, the most important source for funding pensions. The rapid succession of revisions was partly because unlike a number of neighboring countries, particularly Germany (1957), AHV benefits were only adjusted to increasing living costs at a comparatively late stage (pension indexing was only introduced in 1979). The expansion of the AHV, in collective memory, is recalled as ‘Tschudi’s pace’, named after the popular SP member of the Federal Council, Hans-Peter Tschudi, head of the Federal Department of the Interior from 1960 to 1973. The development of private occupational provision was also spurred on by the expansion in public provision: the number of pension plans and those paying into them steadily increased. Life insurers also positioned themselves in the pension plan market and managed a growing number of pension plans, primarily for small and medium-sized companies.

The expansion of both the AHV and the privae pension plans helped reduce society’s anxiety about aging. The image at the beginning of century that old age brought poverty was gradually replaced by the ide of a financially secure retirement. The widespread introduction of old age pensions turned retirement into a special phase of life. This profound change was accompanied by ever-greater demands on the old age pension system as well as a basic discussion about how the system was to be organized in the future. The introduction of supplementary means-tested benefits to the AHV already filled a number of gaps in the Swiss pension system in 1965. These benefits were originally intended as a transitional solution, but the high number of elderly people receiving them showed that of many them continued to live in difficult or even precarious economic conditions. Pension funds only partly helped resolve the problem, as they at the time only reached a limited group of employed workers – very few women and those with low incomes were in these pension plans, for example (Statistics).

Should benefits remain low, or, instead, be increased in order to offer a higher replacement rate of previous income? Instead of expanding state old age pensions, shouldn’t everyone participate in an occupational pension plan? These options called into question the tacit division of tasks between the AHV and the private pension plans and highlighted the growing interconnectedness between the two. These debates arose in the 1960s at the time when the three-pillar concept was articulated. This system sought to keep the development of the AHV (first pillar) within a limited scope and, at the same time, strengthen the key role of pension plans (second pillar) and individual savings (third pillar). Advocates of private provision and in particular life insurers rallied behind this idea. The three-pillar system soon became the counterproposal to the "people's pension" concept put forward in the same period by the Communist left and the left wing of the Social Democratic Party. Both “people's pension" projects called for a massive expansion of AHV benefits. Furthermore, they criticized the private management of pension plans and demanded stronger regulation of occupational provision or even its abolition. The people's pension model was, however, far from achieving consensus on the left. Hans-Peter Tschudi as well as numerous trade unions emphasized the importance of joint management of pension plans by business and labor representatives and strongly rejected the idea of people's pensions.

Between 1969 and 1972, the two concepts competed against each other in conjunction with three popular initiatives. While the political right, including insurers and employers, favored an initiative based on the three-pillar model, the left put forward two initiatives which backed different forms of people's pensions. The counter-proposal prepared by Hans-Peter Tschudi ultimately adopted the principle of the three-pillar model. It essentially combined the development of a compulsory second pillar with a simultaneous increase to the AHV pensions, thus addressing the concerns of those who had advocated people's pensions. Voters strongly favored this counter-proposal on 3 December 1972.

The 1972 vote confirmed and consolidated the division of tasks between the AHV and private occupational provision. However, it provided no answers about how to implement what was now a mandatory second pillar. The economic downturn delayed the implementation of the initial legislative proposal, one opposed by the private pension lobby which was determined to minimize governmental influence on pension plans. The federal Act on Occupational Old Age, Survivors’ and Disability Provision (BGV) was finally passed in 1982 and entered into force in 1985. It represented a minimal framework that nevertheless substantially increased the number of people covered by pension plans – benefiting women in particular. With respect to setting benefits and investing pension reserves, however, the BVG largely guaranteed the autonomy of existing pension funds. For instance, the act did not stipulate a minimum amount for benefits offered by occupational pension plans.

Switzerland stands out internationally due to the increasing importance of the capitalization process (the ‘second pillar’) and due to its large number of pension funds. Around 1980, Switzerland had nearly 10,000 active pension funds, compared to only a dozen or so in the Netherlands, though these few Dutch funds covered entire sectors.

Old Age Pensions and Pension Policy at the Turn of the Century

No further fundamental changes have thus far been made to the basic structure of the provision system established in 1985. The three-pillar model has become the established basis of old age provision. It wasn’t until the beginning of the 21st century that the future of the AHV and occupational provision were jointly discussed. In both areas, debate increasingly focused on the long-term preservation of old age pensions.

In the case of the AHV, a shift of pace and perspective since the 1970s can be observed. The first eight revisions to the AHV, carried out in brief intervals between 1948 and 1972, were characterized by the expansion of pension provision. The next three revisions occurred at longer intervals and were limited to optimizing existing benefits, notably for employed women. There has been a clear push since 2000 to cut costs and to ensure the future financing of the AHV. Slow economic growth, the increase in demographic aging, and free-market criticism of the welfare state have had a lasting influence on the debate. In addition, AHV revisions have become increasingly contentious. Following a referendum, the first of its kind, against the ninth revision of the AHV (which was nevertheless accepted in 1979), the tenth revision took more than a decade and gave rise to intense controversy. Raising women’s retirement age – a measure presented by SP Federal Councillor Ruth Dreifuss as a necessary quid pro quo in order to improve the old age pension situation of women – was included in the final reform package which was passed in 1995. The cost-cutting measures included in the eleventh revision proposed by FDP Federal Councillor Pascal Couchepin also faced tough opposition. The political left and the trade unions contested the eleventh AHV revision with a referendum, and this revision was rejected by voters in 2004 and again by Parliament in 2010. Regardless of these developments, the AHV proved highly stable – despite economic crises, demographic aging, and a doubling in those entitled to pensions. Their number rose from one to two million between 1980 and 2010. From 1975 to 2005, AHV expenditure increased from 5.6 to 6.6 percent of GDP, an increase of less than 20 per cent.

The development of private provision, at least until the early 2000s, took place outside of the political limelight. From 1978 to 2008, the proportion of those covered by a private pension plan increased from 50 to 85 per cent of the working population. The number drawing a BVG pension soared from 300,000 to 900,000 (this corresponds to 30 or, respectively, 50 per cent of those who drew an AHV pension). These figures explain the increase in BVG expenditures, which have more than doubled since the mid-1970s. They grew from 2.8 to 7.7 per cent of GDP between 1975 and 2005, thereby exceeding AHV expenditures. During the same period, the number of pension funds fell by three-quarters (from 10,000 to 2,400); pension funds also became important institutional investors. Within 30 years, the assets managed by occupational pension funds increased from 82 to 660 billion CHF, or from 54 to 123 per cent of GDP. The growing importance of occupational provision within the pension system as well as a financial context characterized by demographic aging and recurrent instability in the financial markets have, since 2000, contributed to increasingly politicized debate on old age provision. The first BVG revision of 2003, which envisaged improved access for low-income workers and an initial reduction in the conversion rate used for calculating pensions, was able to come into effect without triggering a referendum. In 2010, however, a further reduction in the conversion rate was met by broad opposition from the left and was rejected in a popular plebescite. While these actuarial parameters had been long been left to insurance experts, they now became the focus of intense political debate.

Reforms at the beginning of the 21st century

The interaction between the AHV and the pension funds has shaped the hundred-year history of old-age provision. By comparison, provision for individuals has remained marginal. Nevertheless, AHV and pension funds were rarely addressed together by politicians. It was not until "Altersvorsorge 2020" was suggested, a combined reform of the first and second pillars, that discussions of the future of old-age provisions were coordinated and combined for the first time. But in September 2017, the electorate narrowly rejected this proposed reform, largely due a planned increase in the retirement age for women. The Federal Council decided subsequently to separate AHV revision from pension fund revision proposals, an impasse only partly resolved in 2019 by a combined AHV/tax reform proposal. Adopted in May 2019, this reform proposal guaranteed the AHV additional revenues, funded by the federal government, enterprises, and the insured themselves. Contributions to the AHV rose slightly, and the age of retirement remained unchanged.

For this reason, the Federal Council launched the "AHV 21" project in 2019. This project was narrowly accepted by voters in 2022 and represents the first comprehensive reform after a long period of deadlock. The AHV reform is intended to allow a more flexible transition from working life to retirement. With this reform, the "retirement age" in social insurance law will be replaced by the "reference age". The reference age is the age at which the AHV pension can be drawn without any supplements or deductions. If a person decides to retire earlier or later, this has a financial impact on the amount of pension entitlement. The introduction of the reference age is intended to create incentives to remain in (part-time) employment for as long as possible. The reference age for women will also be adjusted to match that of men and is currently (as of 2024) set at 65 for both genders. This adjustment means a de facto increase in the retirement age for women from 64 to 65. The increased flexibility and change in the retirement age as well as the additional funding of the AHV through a VAT increase of 0.4 percentage points to 8.1% should safeguard the funding of the social security system in the medium term.

The initiative "For a better life in old age" submitted by the Swiss Federation of Trade Unions was approved by the electorate in 2024. It seeks to improve the financial situation of pensioners with a 13th AHV pension - especially for pensioners with limited financial resources from occupational and private pension schemes. It is the first successful popular initiative that proposes an expansion of the welfare state via the AHV. How the increase in the AHV pension is to be funded has not yet been determined. Increasing VAT or higher wage contributions are conceivable. What is certain though, is that pension provision will remain a political issue in the face of demographic change.

Literatur / Bibliographie / Bibliografia / References: Leimgruber Matthieu (2008), Solidarity without the state? Business and the shaping of the Swiss welfare state, 1890–2000, Cambridge; Leimgruber Matthieu (2010), La doctrine des trois piliers: Entre endiguement de la securité sociale et financiarisation des retraites, 1972-2010, Yverdon.

(09/2024)